By Matthew Lee

We republish in full Matthew Lee’s excellent essay on the unfolding confrontation between students and university management across the country. It was originally published by the 68 collective.

We are in the midst of one of the largest student rebellions since the 1970s1. 200 students at the University of Manchester have been on rent strike since October 23rd. After occupying an empty university accommodation block they won a 30% first term rent reduction equivalent to at least £4 million — the biggest student rent strike victory in decades. They aren’t stopping there though, having pledged to continue striking in January to win even more, with at least 600 students already pledging to partake. In Bristol, 1400 students have also been withholding rent since October, in what is the largest student rent strike in decades, and have recently won £3.6 million in rent rebates. These students also plan on continuing their rent strike, and 200 additional strikers have already signed up to join next term. These rent strikes have also inspired countless other campaigns to emerge, from Dundee to Portsmouth, with student groups at well over 30 campuses nationally currently organising rent strikes for the new year. Over 500 students at Cambridge, 350 at Sussex, and 300 at UAL are just some of those who have already pledged to strike at their respective universities. At a very conservative estimate, over 5000 students nationwide are now signed up to withhold their next rent payment.

The Re-emergence of Rent Strikes

The current wave of student rent strikes hasn’t come out of the blue, but rather are part of a more general renewed interest on campuses in rent strikes that has emerged since 2015, starting at UCL. After a successful rent strike at Hakwridge House and Campbell House in 2015, triggered by the poor living conditions, a group of militant students launched the UCL Cut The Rent campaign, in conjunction with other community organisers in London. The aim of the campaign was to target UCL’s high rents and poor accommodation conditions. The Cut The Rent campaign was vibrant and militant, organising a 1000 student-strong rent strike, demos in which they burnt effigies of their Vice Provost Rex Knight, and gained media attention worldwide. They went on to win over £1.85 million in rent rebates, bursaries, and rent freezes. They also inspired rent strikes at Goldsmiths, Courtauld Institute of Art, and the University of Roehampton. The rent strike at Goldsmiths went on itself to win £650,000 in compensation. In an effort to generalise this new wave of student tenant organising a ‘Rent Strike Weekender’ was organized in the summer of 2016, where over 160 students from 25 different campuses came together to learn how to organise and spread student rent strikes. At the same time the Rent Strike network was launched.

The Continuation

Following the success of 2016, student rent strikes were organised again at UCL in 2017 and 2018, at Sussex in 2017, and at Bristol in 2017 and 2019. Varying in their size and success (although none reached the size of the 2016 strike at UCL), they won victories from minor repairs to £1.5 million in rent cuts and freezes. During this time, student organisers also made a concerted effort in the Rent Strike network to build campaigns on new campuses and help build the base for further waves of rent strikes in later years. Numerous training days, campus workshops, national days of action, free education demo blocs, and national coordination meetings were held, including a second ‘Rent Strike Weekender’ in the summer of 2019, attended by over 100 students from all across the country. Rent Strike network organisers also aimed to spread what they’d learnt internationally, giving talks to student organisers in Ireland, Germany and Italy.

The Pandemic

In 2020, as we all know, the COVID-19 pandemic hit Britain and made a lot of the organising methods student rent strike campaigners had previously relied upon — such as doorknocking, flyering, etc. — difficult to do. But it also brought about conditions that produced a new wave of struggle and resistance. During the first COVID-19 lockdown, student rent strikes took place in just under a dozen campuses, involving over 2,000 students. These strikes branched out from university-owned accommodation, the focal site of student renter struggles in recent years, to encompass private accommodation providers and landlords in the private sector.

One of the most impressive rent strikes occurred in Bristol, organised by their Cut The Rent group. Around 120 tenants that rented through the student letting agency ‘Digs’ withheld their rent. Eventually, 50% of them won rent waivers for the duration of lockdown. Another sizeable strike was organized at Lancaster University by the newly formed Lancaster and Morecambe ACORN branch, involving around 650 students. Although there were attempts to coordinate these strikes and agitate for a widespread use of these tactics, such as through Rent Strike’s COVID-19 handbook, these strikes did not develop into a greater organised movement. Although many won, demands varied in character to previous strikes. They were mostly defensive in nature, calling for such things as the ability to cancel accommodation contracts early or an end to poor provision due to the pandemic. Part of the reason for this can be attributed to the conditions in which this organising took place. Traditional organising methods were made impossible almost overnight by the pandemic, and the timeframes organisers had in which to organise these strikes were extremely tight. Students were also facing pressing issues, which these demands sought to alleviate, creating an atmosphere where it would have been significantly harder to convince student rent strikers not to simply cut their losses once these initial demands had been met. The fact that we therefore saw a wave of rent strikes of this size is, in itself, testament to the hard work of local organisers, and the experimentation of online organising methods during this period has certainly contributed to a collective knowledge that has been used by organisers in the wave of rent strikes currently unfolding. In addition, these strikes proved that rent striking could be utilised at more than just the few universities that the tactic had seemed to have been stuck in during the prior five years. In this sense, despite certain shortcomings, this earlier wave of rent strikes played an important role through being a key stepping stone in the development of the organisation of student tenants.

There are many aspects that the student rent strike movement since 2015 can be proud of, and that other movements can take inspiration from. In a period in which, for a large part, the student movement has found itself in decline, student rent strikes have provided a beacon of hope where students have won, and proven militant collective action is the powerful tool in our arsenal. The movement’s focus on ensuring the intergenerational transfer of knowledge is also important — far too often, movements come and go, with a variety of history, tactics and expertise lost in the process. Knowing what’s won before, and what’s been done to win, is key to building movements that last beyond individual organisers. Through the work of the Rent Strike network, generations of student rent strike organisers have worked to ensure this knowledge is recorded and passed down. This has helped lay the groundwork for the movement to continue and grow in strength and ability. Finally, the outward facing nature of the rent strike movement has helped see its influence extend outside of university campuses, and into working-class communities all over. Our movement has not just aimed to win a bit of cash for students then and there, but to more generally learn effective methods of organising and class struggle. Even though, due to certain differences in social composition, rent strike tactics may not be utilised as effectively outside of university spaces, our movement has still produced a number of militant organisers for struggles beyond the campus. This includes individuals who have been directly involved in the formation and building of tenant and community unions that are currently thriving, as well as in other social movements and the labour movement.

Lessons Learnt

However, there have certainly been areas in which our movement has failed to reach its full potential. The lack of any formal structure for the Rent Strike network has meant that the continuation of our movement has often fallen on a small number of dedicated organisers. Allowing the maintenance of the general mechanisms of the Rent Strike network to be reliant on the actions of a small number of individuals, has not only put the network in a vulnerable position, but also impedes on its ability to coordinate activity to the greatest possible extent. This situation has also created a space often subject to an informal and subtle social hierarchy, making the network’s activity less democratic and accountable in the process 2. The failure to create formal structures within the Rent Strike network is, in my opinion, an important issue that must be addressed with urgency if we want our movement to unleash its full potential.

Despite its many successes, the student rent strike movement has also failed to create long-term bastions of support in more than a few campuses, mostly in places where the student movement has been traditionally strong. Although work was put into trying to break out of this situation, and build strength locally in places beyond the typical sites of student struggle, these efforts obviously haven’t been enough, and failed to be intensified. Due to this, the student rent strike movement has previously never reached a point in which it has been strong and coordinated enough to take on capital nationally, and win demands outside a localised setting. However, we find ourselves now in a position where it could be possible to break out of this situation…

What Is Happening Now?

The situation now is extremely exciting. Not only have we seen first term student rent strikes for the first time in who knows how long, but these strikes are large, militant, already winning big, and spreading at an incredible pace. This is no small part to tireless hard work of student rent strike organisers up and down the country. The combination of an incoming fresher population pre-politicised by movements such as the school strikes for climate and Black Lives Matter, the pre-existent upsurge of interest in rent strikes on campuses since 2015, and the response of universities’ senior management and the government to the COVID-19 pandemic, has created fertile ground for a wave of rent strikes to occur. Additionally, these rent strike campaigns, unlike those at the start of the pandemic, have had more time to make preparations, and have the organising experience and knowledge of prior rent strikes during COVID-19 at their utilisation. These rent strikes are not purely spontaneous events solely brought about by the conditions of our time, but rather an intersection of spontaneity, local initiative, and long-term organising projects, such as that of the Rent Strike network 3.

The Expansion

What has recently caught most people’s attention is the scale and pace that these strikes are spreading across the country. This is possibly one of the most exciting developments in this wave of rent strikes - 2021 is already set to be the biggest year for student rent strikes in decades. I believe there are a number of key elements responsible for this. The first is the example already set by the rent strikes in Bristol and Manchester. These strikes, both large and militant in character, have shown students not only that it is possible to organise a rent strike, but that it is only through collective, militant action that students can win against the marketised university. The second is the timing of these original strikes. By being organised, and winning, so early on in the academic year, they have helped spawn a number of other campaigns elsewhere also earlier in the year than usual. In the past, copycat campaigns have appeared later in the academic year, when students are typically busier with exams and coursework, and pre-existing student organisers are more burnt out. Thirdly, the militancy of the strikes in Bristol and Manchester — in winning big concessions, and using that as a basis to continue and grow their strikes - has broken constraints in our collective imagination to what can be won by this sort of action, and in doing so has encouraged a concurrent growth in confidence amongst prospective rent strike organisers across the country. The fact that the day after Manchester’s rent strike victory was announced traffic to rent-strike.org increased over seven fold, is just one indication of this. Lastly, it could also be argued that the numerous lockdowns, tiers and all the other restrictions being imposed have assisted in this spread of student militancy too. When you’re stuck inside your room all day, there’s nothing much better to do to pass the time than organising a rent strike!

The Initiators

Another exciting development that has occurred in this wave of rent strikes, is the fact that the vast majority of them are being led and organised by students (mostly freshers) living in university accommodation. This is a change from the past where rent strikes and housing campaigns on campus were often initiated and led by older student organisers, who themselves no longer lived in university accommodation. This shift is significant. Not only does the positionality of these students place them in the strongest position for successful student tenant organising, but also furthers the possibility for these strikes to spread past traditional strongholds of the student movement, by not relying on an older cadre of organisers, and by being able to be generalised to a greater extent than they ever have before. This high level of self-organisation has also arguably encouraged an organic rank-and-file consciousness. One example of this is the willingness of rent strike campaigns to work outside and against institutional structures (such as that of Student Unions) when these structures do not act in their interest and seek to curtail their militancy.

The Demands

A further important development to note in this wave of rent strikes is within their demands. In the past, rent strikes have been organised around almost exclusively demands relating to student housing, and specifically within it, rent prices and accommodation conditions. However, within this wave of strikes, we are seeing a number of direct and indirect demands outside this typical realm, with demands emerging relating to cops off campus, university workers, institutional racism, sexual harassment and assault, and the resignation of senior management figures. Although I would believe it incorrect to categorise any of the previous student rent strikes as ‘economist’, the current wider mobilisation of student rent strikers under wider, rather than mostly economic, demands is a very welcome development. Through doing so, these campaigns are proving that rent strikes aren’t a tactic simply confined to housing, but rather a tactic that utilises the collective power of student tenants and can be used for political intervention. This current development is building the base for the potential utilisation of rent strikes in other struggles on campus — such as in solidarity with striking university workers.

The Coordination

Finally, the coordination occurring in this wave of student rent strikes is an important development. Although in previous years there has been a high level of coordination between student housing campaigns, through the Rent Strike network and other bodies, the level of coordination we are seeing after such a rapid expansion of this movement is quite something. A large part of this can be attributed to the continued agitation and efforts of rent strike organisers at Manchester and Bristol, as well as a wider acknowledgement amongst those involved in this wave of strikes that movement-wide coordination is key to building collective power. Where it could be argued the previous wave of COVID-19 rent strikes failed, this wave of strikes is succeeding, which is a very welcome development indeed. There is important and vibrant discussion constantly happening in the forums that rent strike organisers are using, that are helping to gradually cohere the movement nationally. That being said, the real challenge of coordination will occur in the new year, once rent strikes on other campuses begin, things get busier, and the question of how to continue this level of movement-wide organisation past this academic year and this wave of rent strikes becomes more pressing. It is therefore important that local organisers across the country don’t neglect these coordinating efforts as the year progresses, and maintain and build upon the levels of coordination currently occurring.

Considering Potential Perils

Despite these exciting developments, which signal the new political possibilities opening up in the realm of student rent strikes, there are also a number of potential pitfalls that, the movement must aim to avoid.

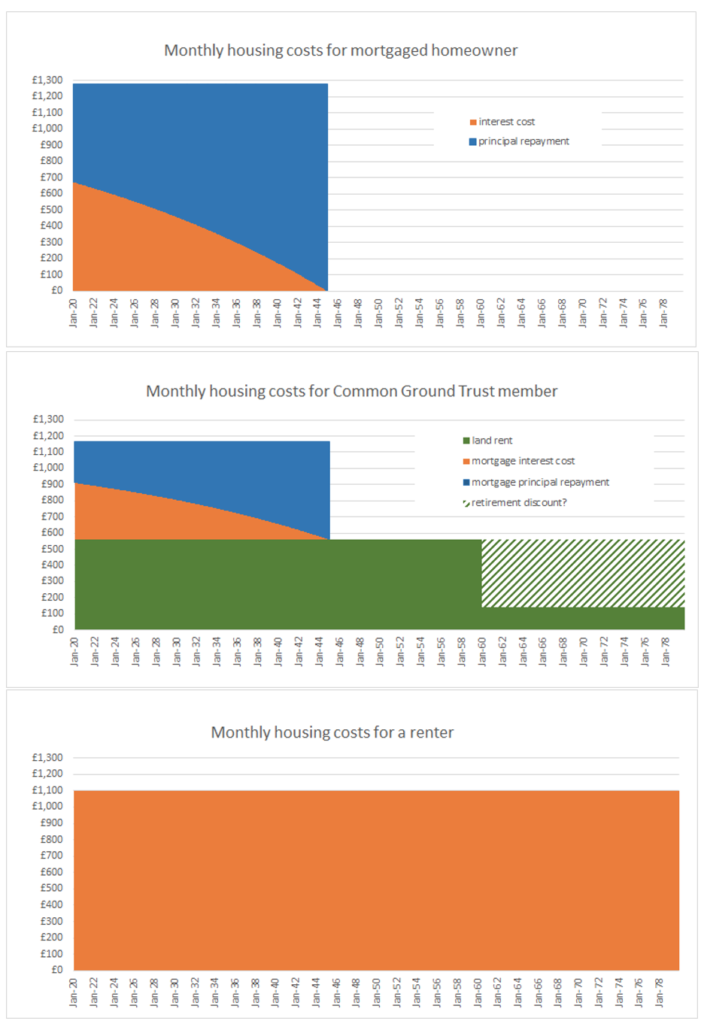

The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed many students to the tipping point, and in the process created a more fertile ground for mobilising students towards militant, collective action such as rent strikes. However, it’s important, in regards to long-term organisation, that we don’t frame our demands and tactics as being solely produced by certain exceptional circumstances created by the COVID-19 crisis. Although it’s hard to envisage at the moment, there will (hopefully) be a time in the near future where these pandemic conditions no longer exist. If we play too much on the exceptionality of our current circumstances, and into rhetorics of how we deserve certain demands because of the current deviation from normality, then we risk reinforcing and legitimising the system that puts us into constant crisis. Student housing, and more generally, the concept of rent, was exploitative before we were launched into this pandemic4. By framing demands and tactics as being a result of a lack of normality, we are contributing to the formation of a political consciousness that argues that ‘normal’ was tolerable, and consequently, will take us as a movement backward. We must accentuate the importance of building a collective consciousness that is against rent and the capitalist housing system in and of itself, and not sacrifice this project in pursuit of short term gains and mobilisations.

In a similar vein, it is also important that we also don’t fall into consumerist arguments in our organising. We don’t organise rent strikes because of a failure of contract, or because a ‘service’ has reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic, but because we are against the very existence of rent itself. As it was so well put in the Rent Strike network’s COVID-19 handbook, “we don’t just strike for ourselves; buried within every rent strike is not just the hatred of a particular landlord, but the property-owning class in itself, as a whole. Exposing this part-in-the-whole and the whole-in-the-part is what unleashes class consciousness, the necessary condition for the building of class power, and ultimately the overthrow of capitalism”5. In maintaining a rent strike movement that is focused on building class power, we must reject arguments and slogans that exist within the remit of capitalism’s logic, and always start from the basis that changing the housing system means making foundational changes to the political and economic structures of society 6. We must therefore aim to use tactics that are outside and/or aim to subvert current legal, economic and social structures, and make demands that aim to transform student housing, and thus push our movement forward by opening up new terrains of struggle, rather than allowing capital to pacify and manage our dissent.

Following from this, it is important we ensure that those being recruited into rent strikes are politicised by them, rather than just passively involved. This is not only to ensure that the strike can be as victorious as possible, as a politicised population of rent strikers opens up more possibilities for blockades, pickets, and other forms of disruptive mass escalation tactics, but also ensures that our rent strike organising doesn’t lead to a political dead end. The aim of organising student rent strikes, as previously mentioned, shouldn’t be to solely win some extra cash for students in halls, but rather also to unleash class consciousness, and build class power, through the process of taking militant collective action. Reflecting on the victorious student rent strike at King’s Road accommodation at the University of Sussex in December 2017, organised through the then-nascent ACORN Brighton branch, Cant argues that despite its £64,000 victory, “the Kings Road strike didn’t generate a viable base. The student rent strikers had failed to take on the organising burden of their campaign, didn’t participate in branch meetings or support other tenants, and very few became dues-paying members of the union. The strike had proven the concept of a renters’ union…but didn’t result in lasting organisational gains”7. Although Cant’s reflection is focused on the use of the King’s Road rent strike in building their local ACORN branch, his account is a good example of why more generally we must take every opportunity to engage rent striking students in the organising process, to emphasise the importance of their involvement in directing the strike, and using this activity to politicise them. We can do this in a number of ways, such as creating mass democratic structures through which decisions around the rent strike can be made by those on strike, and refusing to act as service providers in our organising, instead focusing on encouraging and empowering student tenants’ to collectively take up this organising themselves. Given their expected size, it would be particularly unfortunate for the true potential of this upcoming wave of rent strikes’ mass character to go untapped, as has happened in strikes past.

Finally, it’s also important we acknowledge the different circumstances under which this organising is taking place with COVID-19, and prepare to overcome the new challenges that will come when this pandemic ends (if and when that ever happens!). This means ensuring successful student rent strike organising methods from the pre-COVID-19 era are passed down into the collective memory of current organisers, and ensuring this organising history is recorded and written down, to be made accessible to future generations of organisers. I would argue that the greatest part of the responsibility for this task lies upon those of us who organised rent strikes prior to the COVID-19 crisis.

Rent Strike Futures: What Else Can Come Out of This?

This current wave of rent strikes is exciting not just for its current potential, but also for the future organising they could inspire and open up. With this wave of rent strikes, we should aspire to solidify a strong network of student organisers, who will be able to utilise the huge wave of student rent strikes this year to build upon its gains, and further generalise the movement in years to come, as well as cement the tactic of rent striking within the general student consciousness.

For A Deeper Investigation Into the University

Further to this, let’s use this wave of rent strikes to locate more points in which we can disrupt the running of the higher education sector. With student rent strikes, we have found a way to disrupt the workings of the financialised university to defend our interests and make gains, through restricting the flow of capital that is so necessary for our institutions to function under the current system. We should not be complacent with this discovery though — quite the opposite. We should use this discovery and the success of the student rent strike movement as inspiration, for further detailed inquiry, between both students and workers, into the composition of the financialised university, locating where our strengths and weaknesses lie, as well as that of the university itself. We also must understand the position of students in the financialised university, and more widely, under capitalism, as well as internal contradictions and conflicts within the student population, if we are to successfully build a powerful, partisan student movement, firmly on the side of the working class. I don’t know through what conversations the renewed focus on rent striking as a tactic within the university emerged back in 2015, but as previous revolutionaries have spelt out for us, there can be no politics without inquiry8, and we must prioritise a greater understanding of the student and university worker populations, and the functioning of our university itself, if we want to help build student and workers’ movements within the university that can take on, and stay ahead of the forces of capital that seek to control and discipline our movement and its tactics.

- Goddard, E. (2011). An Incomplete History of Protest at the University of Sussex 1971-1975.

- Freeman, J. (2013). ‘The Tyranny of Structurelessness’. Women’s Studies Quarterly, Vol. 41:3/4, pp. 231-246.

- Nunes, R. (2017). ‘It Takes Organisers to Make a Revolution’. Viewpoint Magazine.

- Lavin, T. (2020). The Good Landlord is a Myth or, Why Landlordism is Inherently Exploitative (via Greater Manchester Housing Action).

- Rent Strike (2020). Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay: Rent Striking Under the COVID-19 Crisis.

- Madden, D. and Marcuse, P. (2016). In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis. Verso: London.

- Cant, C. (2018). ‘Taking What’s Ours: an ACORN Inquiry’. Notes from Below, Issue 3.

- Emery, E. (1995). ‘No Politics Without Inquiry: A Proposition for a Class Composition Inquiry Project 1996-7’. Common Sense: Journal of the Edinburgh Conference of Socialist Economists, Vol. 18.

Matthew Lee is a postgraduate student in Sociology at LSE, organising with the Rent Strike network and various student-worker solidarity campaigns.