By Isaac Levin Schtulberg

In mid-September university students across the UK left their collective isolation to begin a new year at university. For many, this brought hope and excitement — a year promised to be of the same quality as any prior, with sociable societies, safe face-to-face learning and an abundance of the opportunities associated with starting university. The suspension of in-person teaching within the first week of term quickly clarified to students that these were false promises. In the four months that followed, university management faced furious students, growing rent strike movements and, in the case of the University of Manchester (UoM) where the furore has been felt most strongly, disruptions to the university’s power/finance structure.

I had the opportunity to discuss this with Lotte Marley, a founding member of UoM Rent Strike. UoM Rent Strike is the student group which, in light of the pandemic, withheld rent payments from UoM in order to demand rent cuts, a penalty free early release clause and improved housing standards. We discussed why these protests started, how they succeeded and what lessons can be given to the 35 other universities with students embarking on rent strikes.

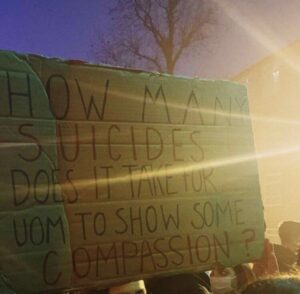

“Broken fridges, pests, mould and students sleeping in hallways”. Lotte described her accommodation in terms befitting a Tripadvisor review of a dingy youth hostel. University halls in Fallowfield average £590 per month per person, almost double the £356/person average for student houses in the same area. It was this, coupled with poor housing standards, that sparked the inferno Vice-Chancellor Nancy Rothwell has faced this year. From freshers week onwards, events unfolded that sullied UoM’s reputation to such an extent that all demands were met, including a 30% rent rebate valued at £4 million.

The ambition of groups like UoM Rent Strike and its allies is to “evolve over time to oppose university marketisation”. Here and now though, with growing rent strikes across UK universities, it is worth reflecting on why the Manchester rent strike won. Applying the lessons learned in Manchester across the whole movement will not only ensure that these victories carry through into the second semester at UoM, but are mirrored nationwide.

While in the past, mobilising students in sufficient numbers may have been a core challenge for student protest groups, this year was different. The COVID-19 crisis has brought clarity to the underlying problems which students face on a yearly basis: extortionate housing prices, overpriced tuition fees and poor quality university services. These problems permeate a student’s existence, but the current situation has brought them to the fore in such a way that students could not remain silent. “Housing was our way in” Lotte explained, “but the problem is so much bigger than that”. The magnitude of student concerns, from their general experience and treatment during the pandemic, has made 52% of students more politicised according to the NUS.

Yet it wasn’t enough to simply recruit a large quantity of rent strikers — the example of the University of Bristol rent strike, where a far larger group failed to have their demands met shows this. “You have to hit them where it hurts, the finances”, a hit on university finances that goes beyond a few weeks' lost rent, but challenges the heart of its business model: reputation and tuition fees. Lotte explained that genuinely challenging UK university’s finances is “all about using the media''. Progress hinged on activists gaining media attention to stain the university’s reputation, jeopardizing future admissions and revenue.

So, how did this play out in Manchester, practically speaking? Initially, the primary challenge for UoM Rent Strike was a lack of recognition, “The university refused to speak with us, they wouldn’t even recognise our existence”. This policy of neglect gave the media little to report and thus, UoM Rent Strike’s efforts were largely in vain.

The solution was to become too visible to be ignored. Escalating the struggle, 15 rent strikers occupied the asbestos filled, derelict Owens Park Tower on campus — a building visible all across Fallowfield. By occupying the structure and hanging banners from it, the rent strike became as impossible to ignore as the building itself. Suddenly, the strikers were not just an abstract community withholding payments to the university, but a palpable group defying the university by risking their health for the organisation's demands. The consequence of this visibility was that the university suddenly felt the heat from the onslaught of media publishing their solidarity with students.

Throughout the first semester the university escalated their repression — putting £11,000 into fencing for the Fallowfield campus and later calling on Greater Manchester Police to be a semi-permanent presence. This purposefully instilled fear into students, illegally stifled protest and harassed students for doing simple chores like laundry.

This police state-like treatment of students was amongst a series of blunders made by the University. Its desire to fence students in after the tragic suicide of first year student, Finn Kitson, was tone-deaf. Enhanced policing on campus created the conditions that allowed for the appalling spectacle of security racially profiling Zac Adan by inexplicably pinning him against a wall. Rothwell’s overt lie on BBC Newsnight over falsely claiming that she had contacted Zac to apologise humiliated the university further. These blunders, coupled with the pressure of the student protests continued to drive the media cycle, tarnishing UoM’s reputation to such an extent that a fear set in. A terror so strong that any for-profit organisation would U-turn in the name of damage limitation; the risk of reduced inflow of new customers, and thus, fear of lost revenue. “It was all over social media,” Lotte explained, “UoM students complaining about their experience and year 13s openly deciding against applying for Manchester due to their actions.” By becoming impossible to ignore, and astutely exploiting the university’s blunders, the strikers had sowed the seeds of the university’s capitulation.

Universities elsewhere may not be so foolish as to simultaneously ignore and mistreat students while they express their concerns. However, the Manchester experience teaches rent strikers a crucial lesson — the largest risk to any university is a loss of reputation and subsequent reduction of future admissions. Other rent strikes must, by any means necessary, use the media to emulate the visibility of Manchester's campaigners. With protest visibility follows media attention, forcing universities to realise the revenue at stake.

Most people are not in a position to oppose universities so directly, however, speaking with Lotte clarified the necessity of imploring students, parents and the general public to openly voice disgust with how universities are treating students. Universities must understand that their treatment of students is a primary concern for those applying to university. Only when we, the residents of this country, show a refusal to pay tuition fees of £27,725 to universities who mistreat students can we expect a genuine change in university culture. A change from students being customers to extract revenue from, into one where students and university staff receive the treatment and respect we afford to one another; deserving to have their thoughts considered, their health and wellbeing assuredly prioritised.

You can follow and support the rent strike movement via Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

Isaac is a Politics and Philosophy undergraduate at the University of Manchester, a researcher for the Peterloo Institute think tank and a volunteer at Greater Manchester Housing Action.

5 January 2021