By Beth Stratford (@beth_stratford)

Buy To Let landlords have played such a big role in inflating the current housing bubble, that serious attempts to rein in landlord extractivism would likely trigger a house price crash. The vast majority of voters are home owners. So how can we persuade governments to end the exploitation and precarity suffered by renters?

Introduction

Over the last two decades, the proportion of households trapped in Britain’s private rented sector has doubled, from roughly 10% to 20%.[1] I use the word trapped deliberately, because the survey data is clear: Only 6% of people want to rent privately, and most of those only want to do so temporarily, due to the expense and instability of it.[2]

Private renting has not increased because millions more households want to line the pockets of a landlord. It has increased because the attraction of landlordism has proved irresistible. Landlords have piled into the housing market, outbidding first time buyers.

Rents have grown from around 10% (pre-1980s) to around 36% of renters’ income (since the mid 1990s)[3] not because homes in the private rented sector have become vastly more comfortable and spacious. Rents have soared because the balance of power between landlords and private tenants shifted dramatically in favour of landlords.

To reverse these trends and end the parasitic relationship between landlords and tenants, we must overhaul the rights and obligations of landlords. Increasing the subsidies available to low income private renters (housing benefit), or first time buyers (Help To Buy), are not long term solutions to the injustices of the housing market. Both forms of subsidy may benefit the immediate recipients, but they also increase effective demand in the market and thereby push rent and house prices even higher over the long term.[4][5]

By contrast, legislation to control rents, end no fault evictions, enforce decent home standards and tax away the unearned capital gains of landlords could permanently end the exploitation and insecurity experienced by private renters, fund the expansion of social housing and encourage landlords to sell up and find more productive and socially benign ways to invest.

But the purpose of this essay is not to rehearse the case for such policies. The urgent need to strengthen tenants’ rights, expand social housing and end the treatment of homes as financial assets has already been widely discussed — in petitions, reports and consultation responses, at protests, party conferences and academic events.

Instead, this essay will focus on the elephant in the room: the fact that reducing the scope for landlords to extract unearned incomes will — all else equal — reduce house prices. And with nearly two thirds of households still living in homes they own, and the stability of our entire economy threatened by falling house prices, no government is going to deliberately trigger deflation in the housing market.

This is a serious barrier to change, and those of us who want to see an end to landlordism need to start talking about how to overcome it. This essay is intended to provoke that long-overdue discussion. The first section looks at why policies to discourage landlordism are likely to trigger a crash in house prices. The second section proposes one possible way out of this conundrum.

Denting the profits of landlords will trigger a fall house prices

Those who think that we can clamp down on landlordism without causing a house price crash must look more closely at the evidence on house price booms and busts. Where house prices diverge from incomes primarily because of shortages of housing (relative to housing need), there is little risk of a sudden drop of house prices. In that context, house prices can only be brought down slowly by increasing the housing stock. But where house prices diverge from incomes because of easy mortgage lending and demand from investors, the market becomes bubble-like, and price rises become vulnerable to sudden reversal. A small change in the political or economic context can effect the confidence of banks or investors, and trigger a very large change in prices.

In the UK the data is very clear: the gap that has opened up between incomes and house prices over the last quarter century cannot be explained by shortages of supply relative to housing need. We had a greater surplus of houses compared to households in 2008 than we did in 1991[6] (when the average house price was £55,000[7]). The government’s own house price model suggests that even if the number of homes had grown 300,000 every year since 1996, far outstripping the growth of households, the average house today would be only 7% cheaper.[8]

To explain the unprecedented divergence of house prices and incomes we must look more broadly at what has been fuelling the fierce bidding war in the UK housing market. What political and economic circumstances might have led to an increase in the number of bidders in the housing market, and in the amount that these bidders are inclined and able to bid? I have answered this question in detail in Chapter 3 of Land For The Many[9]. Here I will emphasize three key factors:

- The dismantling of tenants rights: Between 1915 and 1989, Britain, like many other countries, legislated to control rents and to ensure tenants could not be evicted without reason. Margaret Thatcher’s Housing Acts of 1980 and 1988 dismantled these rights. Meanwhile, a dramatic shrinking of social housing stock following the introduction of Right To Buy helped to create a captive market of households with no feasible alternative to private renting. These two developments created the conditions for a dramatic rise in rents (rents tripled as a proportion of renters’ income between 1980 and 1994[10]), and boosted the attraction of landlordism.

- The availability of easy mortgage credit: During the 1980s and 1990s there were seismic changes in the UK mortgage market – including the lifting of various restrictions on banks and building societies, the growth of securitisation,[11] and the lowering of the Bank of England base rate. The result was a flood of cheap and easy mortgage credit. Domestic mortgage lending expanded from 20% of GDP in the early 1980s to over 60% now, exerting enormous upward pressure on house prices.[12] Particularly significant was the introduction, in the mid-1990s, of Buy-to-Let mortgages for small-scale landlords, which assessed buyers’ credit-worthiness on the basis of rental yield from the property, rather than the buyers’ existing income. This easy finance gave landlords a significant advantage over first-time buyers,[13] and the number of outstanding Buy-to-let mortgages increased tenfold between mid-2000 and 2007.[14]

- The failures of tax policy. The deregulation of tenants rights and mortgage finance kick started house price boom, but the expectation of making capital gains from rising land values turbo-charged it. A better designed tax system — including, for instance, high taxes on the capital gains on investment properties — would have deterred this speculative investment and helped to capture some of the eye watering increases in land value for the public. Instead our tax system actually taxes unearned capital gains from property investment at a lower rate than earnings from going out to work.

Until very recently, Buy-to-let landlords also enjoyed tax breaks in the form of Mortgage Interest Relief (scrapped for ordinary households from 2000), and a Wear and Tear Allowance which did not require any proof of investment in the property. These tax breaks, in combination with the cheap finance and deregulated rents, delivered yields that were difficult to match elsewhere.

It is these factors – that turned homes into financial assets and fuelled the bidding war with easy credit — and not housing shortages, that are primarily to blame for the UK’s high house prices. And it is really important that housing justice campaigners grasp the implications of this.

In 2020 Buy To Let still accounted for between a fifth and a quarter of all lending for house purchases[15], so any policies that discourages Buy to Let investment will mean a signficiant fall of demand in the housing market. And since landlords own a fifth of the housing stock, any policy that encourages landlords to sell will create a sudden increase the supply of homes to the second hand market. If new buyers do not emerge quickly to plug the gap left by landlords and speculators in the market, the result will be rapidly falling house prices. Once house prices start to fall, banks will become more cautious about extending mortgages, and households more cautious about taking out large mortgages. Just as demand in the housing market can be inflated by an increase in the availability of bank credit, it can be rapidly deflated by a decrease in availability of bank credit.[16]

In short, any government that brings in fairer property taxation, an end to no fault evictions, rent controls and decent home standards is going to have a house price crash on its hands, unless it finds an innovative way to mitigate this risk.

No government will willingly trigger a fall in house prices

A fall in prices would of course be welcomed by some people, currently locked out of home ownership. But falling house prices also carry huge political, social and macroeconomic risks. A price fall could push a significant minority of households into negative equity, making it difficult to either move house or re-mortgage. This would be particularly problematic for those on interest only mortgages (around a fifth of all mortgage-holders[17]) and those coming to the end of cheap introductory mortgage deals. Mortgage defaults could, in turn, affect the solvency of major banks whose balance sheets are now dominated by mortgage loans. Meanwhile, households worried about their loss of housing equity are likely to cut back on consumer spending, leading to a general contraction of the economy.

Even if the risks of negative equity, banking insolvencies and economic contraction are less serious than I suspect, it is hard to imagine any government daring to diminish the housing wealth of home-owning voters, who still dominate the electorate.

So where does this leave us? Is there any way of shrinking the private rented sector, and ending the parasitical relationship between landlord and tenant, without triggering a destabilising fall in house prices?

A managed shrinking of the private rented sector

I believe there may be ways out of this conundrum, if we can find a way to enable tenants, coops and/or local authorities to buy the properties that come up for sale (and thereby prevent a sudden shortage of demand in the housing market), whilst helping households out of negative equity in areas where a reduction in house prices is unavoidable.

In the remaining half of this paper I offer one possible way of doing this, inspired by a long tradition of land reformers. It is a proposal that I first described in this detail in a report for the Labour Party[18], and which has the benefit of bringing large amounts of land into a form of common ownership, so that the land rents that are ordinarily captured privately, can instead be redistributed according to need.

End landlordism, bring land into common ownership

The Common Ground Trust (Trust hereafter) is proposed as a publicly-backed but independent non-profit institution which would buy the land beneath houses and lease it to members.[19] The Trust would take the form of a commons, where the land is controlled by a community of members, working within a constitutional framework.

People (including housing coops) could approach the Trust when they had found a house they wanted to buy and ask the Trust to purchase the land. They would then purchase only the bricks and mortar. Since bricks and mortar account for 30% of the price of a property on average,[20] this would allow people to put down much lower deposits and take on much lower mortgage debt than is currently the case, particularly in high land value areas. The new buyers would sign a lease that would make them members of the Trust, and entitle them to exclusive use of the land in return for paying a land rent.

When moving house, members would sell their bricks and mortar, while the Common Ground Trust would retain the title to the land.

Although the Trust would be non-profit, it would aim to accrue a surplus which would be pooled and used to fund a Rainy Days and Retirement Discount for members. This would help to improve the attractiveness of the scheme, compared to both renting and the mainstream model of mortgaged home ownership, as it would improve security of tenure for members who had fallen on hard times, or were unable to work any longer.

The Common Ground Trust would not replace the need for social housing, which should be expanded in parallel. The Trust would serve an entirely distinct purpose. It would be a vehicle for bringing land into common ownership, with three goals in mind:

- To expand the number of people ready and able to buy a house, offsetting the reduced demand from landlords and speculators. This would make it safe to strengthen tenants’ rights, tax property more fairly and ban Buy To Let mortgages.

- To reduce the scale of land rents that are currently extracted by mortgage lenders and landlords, and to use those rents instead to provide a safety net for members who have hit hard times.

- To give more people the opportunity to enjoy a form of private or mutual home ownership. Even with improved conditions in the private rented sector, and an expanded social housing sector, many people will have an understandable desire for a home they can substantially renovate and invest in.

Example

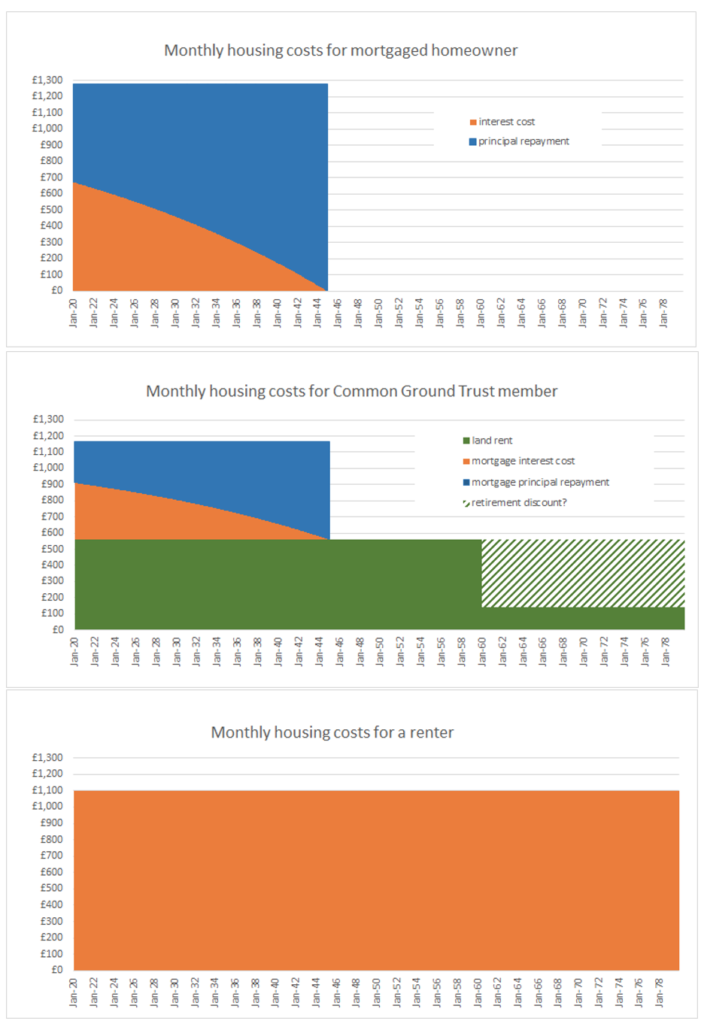

The Smith family find a house they want to buy for £300,000. They have £30,000 in savings – a 10% deposit. If they had a higher household income they could qualify for a mortgage to cover the remaining £270,000. In this case, if they borrowed at 3% interest over 25 years, they would face a monthly bill of £1280 (figure 3a). But the Smith’s mortgage lender explains that – based on their income and credit record – the maximum they can borrow is £150,000.

So the Smiths contact the Common Ground Trust, and discover the land accounts for half the total value of the property: £150,000. The Common Ground Trust agrees to purchase the land, and the Smiths sign a lease that entitles them to exclusive use of the land in return for paying a land rent at, say, 4.5%[21] of the sales value of the land, or £563 per month. The Smiths then pursue mortgage finance to cover the cost of the bricks and mortar.

With the land rent as committed monthly spending, the amount the Smiths can borrow drops to £120,000. Let us assume, conservatively[22], that the interest rate also rises slightly to 3.5% to take account of the fact that this is a novel mortgage arrangement and ownership model. But with this loan, and their deposit of £30,000, they have enough to purchase the bricks and mortar.

Their monthly mortgage repayment costs are £601, bringing total monthly housing costs to £1163. Once they have paid off their mortgage, and assuming stable land values, the Smiths can expect monthly costs of £500, until they reach retirement (figure 3b). For comparison, if they were to rent a house like this it would cost around £1100 per month indefinitely (figure 3c).

Figures 3a, 3b and 3c: Comparison of monthly nominal housing costs facing mortgaged home owner, Common Ground Trust member and private renter

How would land rents and house prices be set?

Land valuations are routinely undertaken for the purpose of taxation in places like Denmark,[23] and in recent years the OECD and Eurostat have been working with national governments to improve land valuation practice and incorporate land into national accounting frameworks.[24] A typical approach to land valuation would start with an estimate for the overall property price, based on sales data, and subtract the rebuild costs, to arrive at a residual land value. New computational techniques and big data (revealing, for instance, the price premium arising from proximity to public transport) should make the land and property valuation processes far less painstaking than they might have been in the past.[25]

There is a case for land rents to be regularly updated, to ensure that they stay in line with market values.[26][27] However limits to this variation could be built in to ensure both security of tenure for the homeowner, and solvency for the Common Ground Trust. For example, households paying the basic rate of income tax could have their land rent increases capped at the rate of median wage growth.

When a house already held within the Common Ground Trust system is resold, the resale could happen under one of two models. The Common Ground Trust could fix the land rent, and allow the house to be sold through a normal process of competitive bidding.[28] Alternatively, the Trust could fix the price of the bricks and mortar, based on the rebuild cost, and allow the land rent to be determined by a process of competitive bidding by the prospective homeowners. In either case, the land rent would subsequently track a published land value index (within the aforementioned limits).

In the short- to medium-term, land rents would be used to recover the cost of purchasing the land. After these costs had been repaid, land rents in excess of operational costs could be pooled and used to fund a discount for members who had fallen on hard times, or were entering retirement. The retirement discount would be available only to members who had been paying in for a minimum period, such as 25 years. It would reduce but not eliminate the land rent, partly to encourage downsizing where this is possible.

Who is the Common Ground Trust designed for?

Membership of the Trust would be most obviously attractive for people who want to enjoy a form of home ownership, to gain greater security and agency over their own living space, but who cannot meet the mortgage deposit requirements.

Membership of the Trust would also be open to housing coops which are fully mutual (only controlled by people living in the property) with an asset lock, so that nobody can profit from or speculate with the assets.[29] This co-operative model allows people without any savings at all[30] to escape the private rented sector and gain collective control over their housing. Rising land prices have increasingly acted as a barrier to the establishment of new housing coops at affordable rents. By removing the upfront cost of land, the Common Ground Trust would support the rapid scaling-up and long term sustainability of this sector.[31]

People wishing to release equity from their homes (e.g. in retirement) may also be interested in selling the land beneath their homes to the Trust, especially in cases where interest rates on home equity withdrawal products were more expensive than the Land Rent. Membership would not be available for speculators, landlords or second home owners.

Governance and Financing

The initial capitalisation of the Common Ground Trust would ideally be financed by government. Fairer taxation of property, and the abolition of harmful policies like Help-To-Buy, would improve public finances and help to make this possible. Options for the ongoing financing of land acquisitions include government-backed borrowing and bond issue. The Trust would require an executive that is answerable to the members, and a statutory asset lock to ensure that it is insulated from the whims of future governments. The constitution would ensure that the interests of future members and society in general are not overridden by the immediate interests of current members.

Why not use other demand-side supports in the housing market?

There are of course other ways that the government can reduce the risk of a damaging house price fall. For instance, keeping interest rates very low, loosening mortgage loan-to-income ratios, and extending the Conservative Party’s Help-To-Buy policy are all levers for fuelling demand in the housing market and thus propping up prices. The drawback of such approaches is that they push households deeper into debt and increase the fragility of the macroeconomy. The Common Ground Trust offers a more sustainable and progressive approach.

Conclusions: Common ownership as a non-reformist reform[32]

The Common Ground Trust creates a mechanism for the gradual, voluntary, but potentially large scale, transfer of land – our single most valuable asset - into a form of shared ownership, so that the associated land rents can be pooled and distributed according to need (in the form of discounts), rather than captured by private landowners and banks at society’s expense. It helps to establish in the popular imagination the idea that unearned rents arising from the control of a scarce natural resource should be socialised. And, if the Trust proved popular and expanded its membership, the proportion of land remaining in private ownership would shrink. Thus it would gradually become more feasible to raise land taxes and advance the broader land reform agenda. But even for those uninterested in such objectives, the scheme would offer tangible benefits:

- Aspiring home owners: the Trust would enable individuals, families and cooperatives with relatively small deposits to enjoy a form of home ownership, and with that, a degree of security and autonomy over their living space that cannot be provided even in a reformed private rented sector. This group would otherwise be waiting a long time for home ownership to become affordable.

- Existing home owners: the Trust can help to ensure house price stability, by giving the government a lever for supporting demand in the housing market, even while landlords and real estate speculators are encouraged to find more productive ways to use their wealth.

- Private renters: through these means, the Trust makes it more politically feasible to bring in rent controls, improvements to security of tenure and decent home standards in the private rented sector, and to clamp down on the speculative behaviour that can lead to rapid and ruthless gentrification.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-dwelling-stock-including-vacants

[2] B. Pannell, 2016. Home-Ownership or Bust? Consumer Research into Tenure Aspirations, Council of Mortgage Lenders, October.

[3] A. Corlett and L. Judge, 2017. Home Affront. London: Resolution Foundation, 17.

[4] “Help to buy has mostly helped housebuilders boost profits”, The Guardian, October 21st 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/money/blog/2017/oct/21/help-to-buy-property-new-build-price-rise.

[5] “Housebuilders charge premium for Help to Buy properties”, Financial Times, August 8th 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/d763c9fa-7c31-11e7-9108-edda0bcbc928.

[6] For Great Britain as a whole, 2.9% of the housing stock was surplus to requirement in 1991, compared to 4.3% in 2008. Author calculations, using data from the government’s live tables on dwelling stock and household projections.

[7] https://www.nationwide.co.uk/about/house-price-index/download-data

[8] These results are in line with other studies, including from the Office of Budgetary Responsibility, the OECD, G. Meen at Reading University, and Oxford Economics for the Redfern Review, 2016. See I. Mulheirn, 2018. What Would 300,000 Houses per Year Do to Prices?, Medium (blog), April 20.

[9] Monbiot, G., Grey, R., Kenny, T., Macfarlane, L., Powell-Smith, A., Shrubsole, G., Stratford, B., 2019. Land for the Many. Labour Party.

[10] A. Corlett and L. Judge, 2017. Home Affront. London: Resolution Foundation, 17.

[11] Securitisation is the practice of pooling together and repackaging a number of loans and issuing tradable debt securities sold to investors that will be repaid as the underlying loans are reimbursed. In many cases the loans used to back the tradable securities are mortgage loans (residential or commercial) – in these instances the securities are called ‘Mortgage Backed Securities’ (MBS).

[12] J. Ryan-Collins, T. Lloyd, and L. Macfarlane, 2017. Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing, London: Zed Books.

[13] P. Saunders, 2016. Restoring a Nation of Home Owners: What Went Wrong with Home Ownership in Britain, and How to Start Putting It Right, London: Civitas.

[14] HM Treasury, 2010. Investment in the UK private rented sector, February.

[15] FCA. 2020. Mortgage Lending Statistics.

[16] C. Goodhart and B. Hofmann, 2008. House Prices, Money, Credit and the Macroeconomy, Working Paper Series, European Central Bank, April. J. Muellbauer and A. Murphy, Housing Markets and the Economy: The Assessment, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 24, no. 1 (2008): 1–33. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grn011.

[17] Tatch, J., 2017. Interest-only: coaxing the cat out of the bag. Council of Mortgage Lenders, 15 May.

[18] Monbiot, G., Grey, R., Kenny, T., Macfarlane, L., Powell-Smith, A., Shrubsole, G., Stratford, B., 2019. Land for the Many. Labour Party.

[19] The model is designed for freehold properties but could theoretically be made to work in a more limited form for leasehold properties. We do not discuss this potential model extension here.

[20] Office for National Statistics, 2017. The UK national balance sheet estimates: 2017.

[21]The precise ratio between sales values and rental values varies by region. This figure is based on the average gross rental yield for England and Wales in June 2018. Your Move, 2018. England and Wales Rental Tracker. July 2018

[22] The bricks and mortar could actually be considered a safe form of collateral since the Common Ground Trust could guarantee to repurchase the bricks and mortar at rebuild cost. The rebuild cost of a house is far more stable than land values, and could be made even more so if the maintenance of the bricks and mortar were enforced by a covenant. This would reassure the mortgage lender that if the borrower defaulted on their mortgage, their bricks and mortar would have a guaranteed buyer, allowing the borrower to repay any outstanding debt to the mortgage lender.

[23] A. Muller, 2000. Property taxes and valuation in Denmark. Presentation at OECD Seminar about Property Tax Reforms and Valuation, Vienna 19-21 September 2000

[24] Eurostat and OECD, 2015. Eurostat-OECD Compilation guide on land estimations.

[25] D. Adler, 2017. Home Truths: A Progressive Vision of Housing Policy in the 21st Century, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

[26] If land rents for existing members systematically diverge from the market rates available on new leases, then people may be discouraged from moving house or encouraged to sublet to capture the difference. The further prices and values diverge, the more politically challenging it will be to make a revaluation, and ensure that unearned land rents are properly shared.

[27] It is of course important to ensure that the Common Ground Trust is exempt from any ban on leasehold and ground rents, and any leasehold enfranchisement legislation.

[28] A risk with taking this approach is that if the Common Ground Trust were to underestimate the market rental value of the land, the seller could walk away with unearned windfall gains from an inflated house price. If the Trust were to overestimate the market value of the land, the seller could find it difficult to fetch a fair price.

[29] Currently co-operatives can obtain only a rule-based assets lock and would benefit from a change in legislation to create a statutory asset lock for such corporate bodies.

[30] It is usual for such co-ops to raise capital through issuing loan stock to friendly investors. It is possible for members to invest in their own co-op (through loans or shares) but it is not usually a requirement.

[31] Resilience of the cooperative housing sector would be further increased with a mechanism for ensuring that surplus rents within each housing coop are used for the establishment of new co-ops.

[32] ‘Non-reformist reform’ is a term borrowed from French writer Andre Gorz, who sought to distinguish between ‘reformist reforms’, which subordinate themselves to the need to preserve the functioning of the existing system, and non-reformist reforms ‘which advance toward a radical transformation of society’. A. Gorz, 1968. Strategy for Labor: a radical proposal, Boston: Beacon Press.

Beth Stratford is co-author of 'Land for the Many', a fellow at the New Economics Foundation, and a co-founder of the London Renters Union. She is currently writing a PhD about tackling rent extraction and reprogramming the economy for a finite planet.

Cover photo credit: Siobhan Donnachie.

This piece was made possible thanks to support from the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

31 December 2020