By Aaron Downey

This is adapted from a talk given by Aaron to our recent event 'Is There Power in a Tenants Union?'. You can re-watch the whole event on our Facebook page, here. The piece was first published on the CATU Ireland blog here.

CATU Ireland was properly launched around a year ago, with our first local committee established a couple of weeks before we headed for full lockdown on the island. As a result we have had the strange experience of trying to grow a union in the community (block by block and street by street) with a limited amount of doorknocking, outreach, and in-person conversations that would be necessary for this kind of work. Despite this, we’ve managed to establish footholds across the island of Ireland, approaching 700 members with a dozen locally based committees covering the major cities of Dublin, Belfast, Cork, and Galway. We have organised eviction defences, won back deposits, and forced landlords and letting agents to abide by the aspects of the law they are required to. It’s a start.

To take a step back however, there have been waves of social struggle around housing for centuries on the island of Ireland.

There are several historical Irish examples I briefly want to touch on (there are many more!) that show some tactics that are available for organising around housing in specific contexts. The island of Ireland has historically had a quite unique relationship to questions of land, housing, tenancy, and property for a European country - often tied to our colonial past.

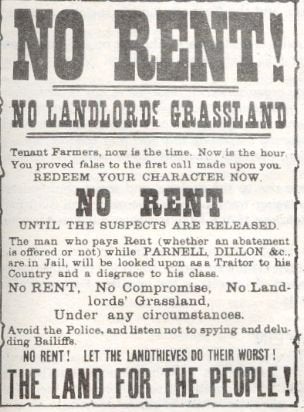

For instance, in the late 19th century there existed a large campaign around fair rent, freedom of sale, and fixity of tenure for tenant farmers in Ireland orchestrated initially by the Irish National Land League. Often tied to the national liberation struggle, and the link between British imperialism and the low quality of farmland and high rent extracted by (usually absentee) landlords, it inaugurated the “boycott” as a tactic of economic disruption, alongside utilising rent strikes, social stigmatisation, violence, and mass meetings to build a tenant farmer class movement, eventually resulting in the introduction of reforms.

The tactics of boycotts also prominently manifested in the US black civil rights struggle in events such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a civil rights struggle that would then be reflected back across the Atlantic, inspiring a campaign to end discrimination against the Catholic minority in jobs and housing in Northern Ireland. Here rent and rate strikes were used as tactics amongst mostly Catholic tenants, for instance to protest the re-introduction of internment without trial in 1971. As a tactic, rent and rate strikes emerged in the context of: a large scale rights movement that would back it up with civil disobedience, the beginnings of a violent conflict in the North, and a Catholic population that were disproportionately unemployed, so often the main form of economic disruption available to them involved withdrawing payments from council housing or gas and electric companies.

Finally then, there was a large scale rent strike in the south of Ireland organised by the National Association of Tenants Organisations (NATO) in 1972. Large scale housing development was initiated at various points post-independence owing to the disrepair of slum-like tenements concentrated in city centres. This had the effect of centralising a lot of poorer families into council housing. At its peak, the strike had over 100,000 families renting from the council on rent strike, and was successful in the introduction of differential rents tied to income nationally.

All of this is to say that housing organising can be disruptive, using economic or social pressures to bring targets to heel. Housing, as part of a system of private profit and wealth accumulation, offers major ways to interrupt this flow of money through things like non-payment of rent. The price of land rests on the assumption it will provide future profit. If producers build e.g. housing, but consumers don’t buy or continue to pay rent, this has massive impacts on developers, landlords, and the wider market. Tenants also have the ability to put pressure on landlords and developers in a variety of different ways that they are simply not used to, for instance picketing. Different contexts offer different organising opportunities: the prevailing political mood at that moment, the centralisation or decentralisation of tenants, or what employment (or lack thereof) means for workplace resistance.

Housing and property has maintained its importance into modern Ireland with the birth of the Celtic tiger accompanied by large scale real estate development and a massive property bubble. Today in Ireland, rents have generally risen across the board since the financial crash of 2008 while incomes have not risen comparably.

Many public sites have been sold off to private developers to build housing stock, some of which is then bought back by the state at an exorbitant rate while the rest goes to fuel the same system of private rental profit-seeking (see O’Devaney gardens for instance). The notion that the market is the most efficient way to deliver a public good has continued even when all evidence points to the contrary. In practical terms, ourselves, or many people we know, have been on the receiving end of illegal, vindictive, or immoral actions carried out by landlords, often to realise a greater share of profit in the current market. As demand for privately rented housing has increased so has its rent, a trend mirrored across many more developed nations. An increasing part of what workers bring home from their workplace in the form of wages is taken by landlords. Homelessness and housing precarity has risen as a result.

Also, in Ireland, in the last 20 years, and often particularly prominent since the financial crash of 2008 we have seen intensifications in struggle against economic issues such as water charges, or the housing system, for feminist/LGBT issues such as the the referenda on same-sex marriage, or the repeal of the 8th amendment, alongside more contained environmental and anti-racist fights such as the Shell to Sea campaign (which began pre-2008 but continued into the recession) or the Kinsale road Direct Provision lock-outs which played a part in the formation of the Movement of Asylum Seekers in Ireland.

These all have combined tactics and tools from mass volunteer doorknocking, direct action, occupations, legal battles, community blockades, and more. While there have been successes such as earning concessions around water charges, or winning referenda, other campaigns and projects have suffered due to a lack of resources, or lack of a clear organising model.

CATU was formed mostly out of the housing struggle and the failure of the previous models of activist-led direct action. The existing organisational forms and strategies had failed to grow a base outside of people who already agreed with us, and there was a strained relationship between the intention of locally-based deep community work and direct action which was more spectacular but also tied less to material differences in peoples’ lives. There was a failure of sustainability and organisational coherence with looser structures, alongside less accountability.

The union was set up as a way to tie housing and community concerns in a more structured and long-term way, organising on a geographical level and not just with renters. Aiming to be a mass membership organisation means campaigning on all issues concerned with “social reproduction”; basically everything that goes into sustaining us so we can show up at work the next day. As a community union it means campaigning on issues that members care about like those mentioned previously; not just those that are explicitly “housing” related. Ireland also historically has had a large amount of home ownership (although this is changing) as the government in the South post-independence subsidised home-owners as a potential bulwark against radicalism. As a union we seek to embrace all tenant organising, defined as broadly as possible as those who do not own their own or are provided with accommodation, alongside community organising as experiences of class on a geographical level can intersect with, but are not tied solely to housing - think for instance community cuts, lack of bus routes, or the concentration of poverty.

With the setup of CATU, we wanted an organisation that can put down deep roots in communities, campaign on issues that matter, and not be fleeting or flyby or get caught in the cycle of electoral politics. We want to highlight the politics of everyday life.

We wanted to exist in, and contribute to, an ecology of other social movements in the community and in the workplace.

Ultimately, what I want is a large mass of people politicised through fighting for themselves on issues that matter to them, with the analysis and tools to take this further and win real systemic change. We only want the earth.

Aaron Downey is the Training and Education officer at CATU Ireland (@CATUIreland).

This piece was made possible thanks to support from the Rosa Luxemburg Siftung.

18 November 2020