By Kerrie McGiveron (@kerriemcgiv)

‘There is no doubt that the Kirkby development will be a very attractive one, and the standards of designs, not only for the layout, but in the individual dwellings will be high.’[1]

Ronald Bradbury, Architect and Director of Housing for Liverpool, 1953

‘I wonder if they built these flats deliberately to hurt us.’[2]

Female resident of Tower Hill, 1974

Kirkby

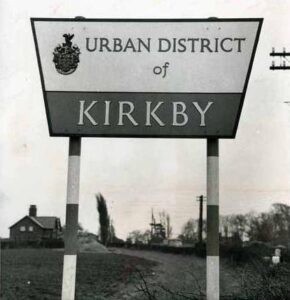

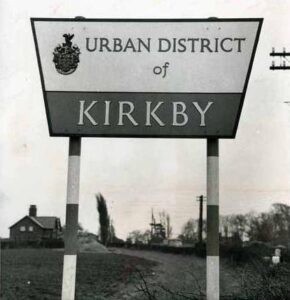

Kirkby, a rural parish made up mainly of farmland, was purchased by Liverpool Corporation to ease the housing crisis in Liverpool city centre in the 1950s. The local press covered the development of the new town, including an article by the Chair of Liverpool Corporation. He assured readers that those relocated to Kirkby would have all the necessary amenities for them to lead a ‘happy and contented life.’[3]

The ambitious slum clearance plan was to move 50,000 tenants from inner city slums into rural Kirkby over six years.[4] However, transport, amenities, and leisure facilities were not provided, resulting in isolation and discontent.[5] The inadequacy of the administration was noted in the local press, with Kirkby being labelled ‘the baby no-one wants.’[6]

A police report by Sergeant Norman Chappell was published in 1972 detailing Kirkby’s social and economic malaise covering crime, housing, and unemployment. The high-rise flats on the Tower Hill estate were a particular cause for concern. Complaints were common in the tower blocks, which were small, poorly insulated with obtrusive plumbing noises, causing considerable psychological distress to the inhabitants. One tenant described the conditions that people were living in the tower blocks as ‘sub-human.’[7] It was reported in the press that the River Alt running a mile through the centre of Kirkby was ‘the worst polluted stretch of water in the world, containing cyanide and arsenic.’[8]

The failings of Kirkby’s town planning were eventually exposed in the late 1970s. An investigation by the Centre for Environmental Studies concluded that ‘policy-makers and planners must carry considerable responsibility for failing to ensure means and resources were available to implement the original plan.’[9] Indeed, some of these people did carry the responsibility in the form of jail sentences. As reported in The Guardian in 1978, builder George Leatherbarrow, leader of the council David Tempest and architect William Marshall were all convicted of corruption for their part in the creation of the town of Kirkby, guilty of accepting bribes for contracts.[10] Amongst evidence cited was the construction of a ski slope which was built over a main water pipe and reportedly facing the wrong way. At a cost of £100,000 the ski slope was demolished without ever being used.[11]

The Housing Finance Act 1971: An Insult to Injury

Edward Heath’s Conservative government introduced the 1971 Housing Finance Act (HFA). Essentially, the HFA raised rents of local authority dwellings and promised rents that would reflect, ‘value by reference to its character, location, amenities and state of repair.’[12] Known as the ‘fair rents act,’ those who could not afford the new rents would be entitled to a rebate, paid for by better-off tenants.[13] However, it was raised in parliament by leader of the Labour party Harold Wilson that the take-up of means-tested payments would probably be low.[14] Labour voted against implementing the act, but the party hierarchy urged Labour councillors to implement the act and negotiate the rent increase to protect tenants, resulting in struggles within the Labour Party and a split over the issue.[15] The lack of organisation at local government level, compounded by impending threats by a central Conservative government hell-bent on getting its way meant that Labour-controlled councils conceded. Adding insult to injury to the poorly built housing on Tower Hill, it was reported that as well as the rent increase, rate rises in Kirkby were the third highest for any urban district in the country.[16]

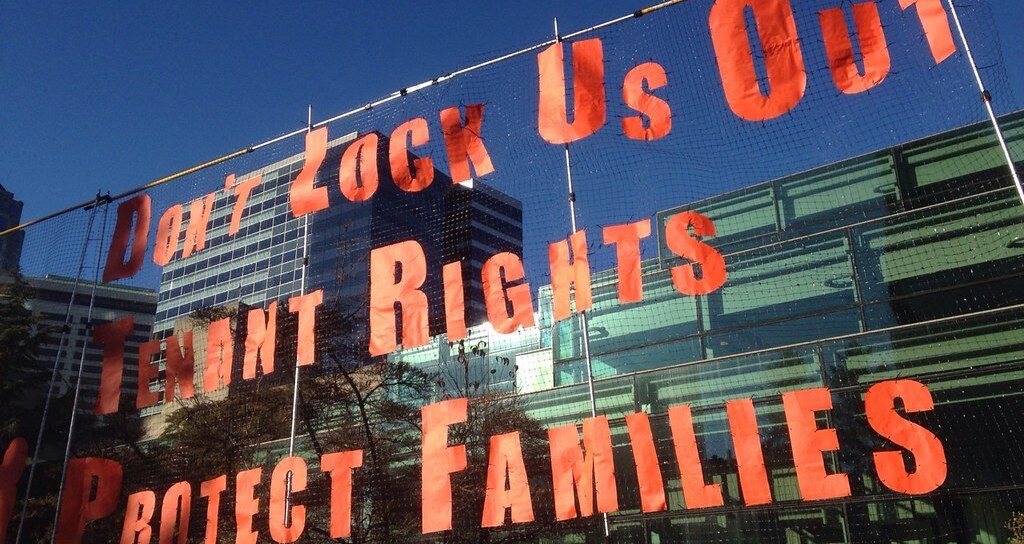

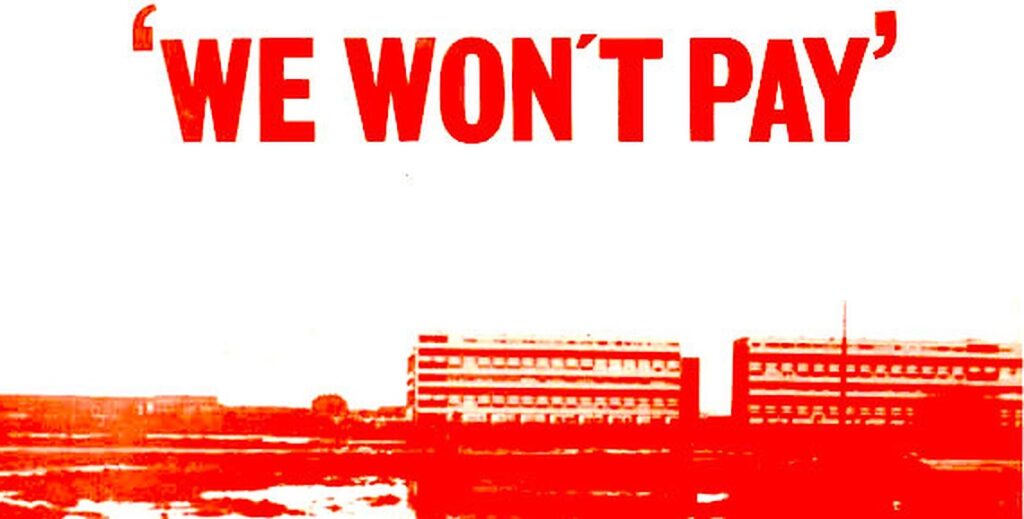

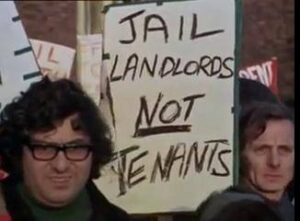

The HFA was set to affect more than 2,000 tenants living on the Tower Hill estate, and despite Labour council leader Dave Tempest’s reassurance that they would press for the ‘lowest possible rent increase,’ tenants were already planning to organise.<[17] Tower Hill Unfair Rents Action Group (THURAG) was formed, made up of residents, the International Socialists, and communist activists. THURAG’s secretary Tony Boyle announced to the local press: ‘as soon as the Housing Finance Act is implemented, the council will have a total rent and rate strike on their hands.’[18] The rent strike would involve over 2,000 residents on Tower Hill, span fourteen months and leave a lasting impression.

‘On Rent Strike’

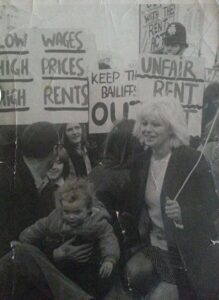

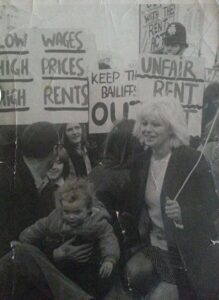

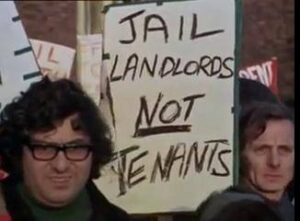

During the rent strike, workers at the BirdsEye factory on Kirkby Industrial Estate who participated in the rent strike marches were suspended. In response, tenants organised a mass picket; women with babies in prams and members of THURAG with loudhailers were joined by workers and dockers.[19] They produced weekly leaflets to keep tenants aware of developments; lobbied council meetings and leafletted local factories for support.[20] The Tower Hill estate was divided into eleven zones, each zone sub-divided and an anti-eviction system put in place. Groups of activists followed rent collectors around the estate to ensure there would be no ‘strike breakers.’[21] Tenants were urged to send their rent demand letters back to sender with ‘on rent strike’ written in ink, and barriers were erected to keep the bailiffs out.

Under New Management

In January 1972, alongside the rent strike at this point in Kirkby was the occupation of Fisher-Bendix. Following redundancies, it began when 18 members of staff occupied the building, hanging a sign above the entrance that simply said ‘under new management.’[22] The occupation lasted five weeks and was covered by the national press, with The Guardian, reporting that 600 workers had taken over the factory.[23] Workers interviewed explained the novel implications of a sit-in rather than a strike, stating that women ‘were as involved as anyone else in the occupation.’[24] The statement issued from the workers called on a complete boycott of Fisher Bendix products, specifically addressing housewives.[25]

By March 1973, attachment of earnings orders were issued to rent strikers to reclaim the debt owed.[26] In response, urged by THURAG, hundreds of people marched the streets of Kirkby. Activists urged tenants to unify in their struggle over rents and rates. In October 1973, court notices were sent to 36 tenants, all of whom refused to appear.

In early December, activists stormed the council offices in Kirkby town centre. Police arrived on the scene, and clashes ensued, tensions were high as the tenants were forcibly turned away from the council buildings.[27] Two rent strikers, Brian Owen and Larry Doyle were arrested. In response, activists set off an air raid siren to alert people and roadblocks were set up. The radical fringe newspaper, Big Flame reported that over 100 tenants marched to Kirkby industrial estate to try and get support from factory workers.[28] When jail sentences were announced there was an immediate walk-out at Anglia Paper Products in Kirkby, and on Sunday the 9th December, there was a demonstration of over 400 people outside Walton jail.[29] Activists used loud speakers to draw attention their cause, and Big Flame reported two coach loads of supporters from Manchester and Oldham attending in solidarity. [30] The newspaper enthusiastically reported that police were overwhelmed by the ‘organised defiance’ of the rent strikers.[31] This also attracted the attention of the national press, with The Guardian reporting that demonstrators had been picketing since the men had been jailed, including Brian’s son, Paul, aged 4 who held a banner reading ‘Release my Daddy for Christmas.’[32]

After 14 months the rent strike ended, and tenants were ordered to repay what they owed at a maximum rate of £1 a week.[33] Amidst the unfolding national industrial unrest, including the miner’s strike and the subsequent blackouts and three-day working week, Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath called a general election, resulting in a hung parliament. Later that year, Labour took charge and repealed the punitive Housing Finance Act.

Although the rent strike in Kirkby was not a victory for the tenants, it would be wrong to dismiss it as a failure. The industrial action at BirdsEye and Fisher-Bendix alongside the rent strike in 1972 signalled a strength in unity among tenants and workers, offering some important insights into how unified resistance, organised defiance and joined-up class activism might continue today.

[1] R. Bradbury, ‘New Ideas in Liverpool’s Biggest Housing Venture,’ Liverpool Daily Post, 29th October, 1953

[2] Big Flame, ‘Notes on a Community Struggle,’ Big Flame, Women’s Struggle Notes 5 June-Aug 1975. Personal archive of K. McDonnell

[3] Bewley, ‘Liverpool’s Greatest Housing Scheme’, Liverpool Daily Post, 2nd May 1950

[4] N. Rankin, ‘Social Adjustment in a North West Town’ in K. G. Pickett, D. K. Boulton, Migration and Social Adjustment, Kirkby and Maghull (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1974), p.10

[5] D. M. Muchnick, Urban Renewal in Liverpool, A Study of the Politics of Redevelopment, (London: Bell, 1970), p.28

[6]‘Urban Status Plea For Kirkby,’ Liverpool Daily Post, 2 April 1956

[7] N. Rankin, ‘Social Adjustment in a North West Town’ in Kathleen G. Pickett, David K. Boulton, Migration and Social Adjustment, Kirkby and Maghull (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1974), p.21.

[8] Kirkby Urban District Council, Health and Housing Committee Report, 12 March 1973, Kirkby, Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) KUDC Box 12/1,

[9] Centre for Environmental Studies (CES) Limited, Urban Resource Centre, Knowsley Metropolitan Council Merseyside County Council, Kirkby: An Outer Estate (Liverpool: 1982) p.7, Kirkby, Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK), R301.54

[10] ‘Builder and council men gaoled for bribes,’ The Guardian, 10th June 1978

[11] ‘Jail for council men who took bribes,’ Daily Mail, 10th June 1978

[12] Kirkby Urban District Council, Health and Housing: Agendas and reports for the Health and Housing committee meetings, 27 September 1971, Kirkby, Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) KUDC Box 12/1

[13] The Liverpool Free Press reporting in 1971, announced that hundreds of thousands of tenants would never claim or receive the rebate that they were owed. The Liverpool Free Press, which was written by three Liverpool Echo journalists and promised to be ‘the news you’re not supposed to know,’ were responsible for investigating and exposing the corruption scandal of the development of Kirkby. Liverpool Free Press, August - September 1971, Liverpool Records Office, Class 072 FRE

[14] See Hansard, HC Deb, 2nd November 1971, column 22 Wilson debated that the fair rents would on average double the rent of council tenants, as well as low successful applications for rent rebates.

[15] L. Sklair, ‘The Struggle Against the Housing Finance Act’, Socialist Register, (1975) Volume 12, p.253

[16] ‘Kirkby attack on ‘crippling rates, ’’ Liverpool Echo, 23rd November 1971

[17] ‘One vote brings Kirkby Rent Act,’ Liverpool Echo, 12th September 1972. Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) Rent and Rate Newspaper Archive 1970-1976

[18] ‘Rent Strike Threat Over Rises,’ Kirkby Reporter, 13th September, 1972. Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) Rent and Rate Newspaper Archive 1970-1976

[19] K. Singleton, Thousands Say, We Won’t Pay! Merseyside Tenants in Struggle, 1968 – 1973, (Saarbrucken: LAP Lambert, 2012,) p.174

[20] C. Oliver, Tower Hill, (unpublished document 2017.) C. Oliver’s personal archive

[21] ‘Liverpool Tenants Say ‘Rent Rise – Rent Strike,’ Big Flame No. 3, September 1972, Liverpool, Liverpool Records Office, M329 COM/36/9

[22] ‘Bendix – how the workers took over,’ Big Flame Leaflet, 1972. Reproduced online https://bigflameuk.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/bendix-how-the-workers-took-over.pdf [Accessed 14th August 2017]

[23] G. Whitely, ‘600 workers stage factory sit-in,’ The Guardian, 6th January, 1972

[24] Big Flame, ‘Bendix – how the workers took over,’ (leaflet), 1972. Reproduced online https://bigflameuk.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/bendix-how-the-workers-took-over.pdf [Accessed 14th August 2017

[25] Ibid

[26] Kirkby Urban District Council, Health and Housing Committee Minutes, 21 May, 1973. Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) KUDC Box 12/1

[27] Behind the Rent Strike Dir: Nick Broomfield (National Film School: 1974) available online https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0anu9hlQ9iA [accessed 21st July 2017]

[28] ‘Rent Striker Jailed – Hundreds Demonstrate outside Walton,’ Big Flame, December 1973, Liverpool Records Office, M329 COM/36/9

[29]‘A Lion’s Den by Rent Strikers,’ Kirkby Reporter, 12th December 1973

[30] ‘Rent Striker Jailed – Hundreds Demonstrate outside Walton,’ Big Flame, December 1973, Liverpool Records Office, M329 COM/36/9

[31] Ibid

[32] ‘Prison picket stops,’ The Guardian, 12th December 1973

[33] Leslie Sklair, ‘The Struggle Against the Housing Finance Act’, Socialist Register, (1975) Volume 12, p.274

Kerrie McGiveron is a PhD candidate at the University of Liverpool. Her research interests include 1970s Britain, the far-left, Big Flame (1970-1984) and the WLM.

On Tuesday 25th January she is speaking at a meeting organised by ACORN Liverpool on the Kirkby rent strikes. All details here.