By Isaac Levin-Schtulberg

As the months since July’s ‘freedom day’ roll forward, those residing in the UK have been reacquainted with a lifestyle that they once considered a stable normality. The daily slog of COVID briefings, statistics and superfluous analysis about COVID-19’s radically transformative long term impacts have become resigned to what many want to be a bygone era.

Weird as it may be considering the increasingly rampant number of daily cases and deaths, it feels as though the memory of COVID-19, and the unprecedented transformation of life that came with it, has begun its gradual decline into what will eventually be a distant memory upon which we will reminisce. Yet, in the analysis of COVID-19’s future consequences, an important topic has been overlooked; how the ensuing economic crisis reflects a growing trend of the financial industry utilising crises as a means to entrench and accelerate the financialisation of housing.

To understand what this means, why it is important and how it is happening, I spoke with two experts in the field; Desiree Fields, a researcher on housing financialisation at the University of California, Berkeley, and LSE visiting fellow, housing and urban policy expert, Glyn Robbins.

Our conversations illuminated a transition from 1980 to the present, a period where housing transformed from a social good into an asset, underpinned by self-serving financial governance, unregulated banking and foreign investment. These changes, or its financialisation – the increasing role of financial actors, markets and institutions in economies – have already created a system which facilitated the destructive 2008 subprime mortgage financial crisis, alongside intense gentrification, extortionate housing costs and declining living standards. Now, with the incipient economic aftermath of the pandemic, we risk witnessing these issues exacerbate as we edge perilously close to a new landscape of global corporate landlordism.

“You’d be remiss to talk about this without starting with Thatcher’s Right to Buy”, Glyn told me. The Right to Buy scheme – where those renting council houses could buy their homes well below market value – marked a huge step in relinquishing governmental responsibility for housing.

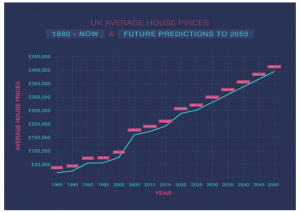

As Right to Buy allowed the working and middle classes to buy their council homes en masse, a speculative feedback loop of house buying, inflating prices and increasing borrowing to buy more houses pushed prices up ever higher. Consequently, in the mind’s eye of UK society, housing transformed from a home, an indispensable public good for all, into a supposedly low-risk asset class that could make you rich.

The average house’s value tripled in the following decade, making homeowners far wealthier. In 1989, unfortunately, the music stopped. The housing market had crashed. Suddenly, the properties bought through Right to Buy were sold to extremely wealthy investors intending to profit in the increasingly expensive rental market. For politicians, this was terrible for votes, for business interests and, for the many property owning politicians, themselves. From then on, a slew of policies, first from the government and then the Bank of England, were enforced to ensure that housing – unlike other investments – never lost value.

Interest rates were continuously cut to encourage borrowing to buy houses after the 1989 crash. Meanwhile, new, increasingly risky mortgage-based financial instruments boomed, allowing the financial services industry to make trillions on the housing market; unimaginably more than the underlying value of the assets that were being traded on capital markets. Accompanying these were hugely risky low-to-zero deposit mortgages, ensuring people who could not afford homes bought them anyway, consequently indebting a generation. Nonetheless, capital kept flowing into the financial industry’s housing securities.

Concurrently, the responsibility for house building shifted, beginning to lay squarely on private property developers. Their chief aim was profit, which meant fewer, more expensive homes were built, increasing housing’s scarcity and its value with it. The combined effect of these changes was that housing became more expensive and the financial industry became totally enmeshed with housing. Regardless of if it was financially viable, more houses were continuously purchased through the financial sector dishing out unpayable mortgages that could then be traded for huge profits on capital markets. This culminated in the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, all the while skyrocketing the price of a house by an absurd average of 1145%.

It cannot be understated just how bad this shift has been for people in the UK. The financial crisis in 2008, a situation created from increasingly risky strategies in the financial industry’s mortgage securities trading, destroyed millions of lives. The austerity policies that followed 2008 made matters worse. Stagnating wages from the crisis and the austerity policies that followed has meant that communities – particularly black working class communities – have been unable to keep up with the boom in rent prices. Communities like Brixton and many more like it, once hubs of black culture, have had their inhabitants priced out.

Despite this system being perceptibly broken, so perilously destructive that the UK is failing to meet the human right to adequate housing according to the UN, it is a totally intentional element of the UK economy. After 2008, for example, the Bank of England utilised quantitative easing (printing money) to buy government bonds (debt) in order to prevent the significant reduction in asset prices normally expected in economic turmoil. This, alongside continually low interest rates, has made sure the returns on investments into government bonds are low and mortgage repayments are less expensive, incentivising investors to buy property, propping up property prices.

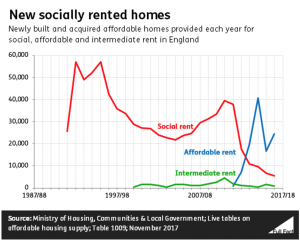

The consequent demand for London’s housing as an investment has allowed 13% of the city’s homes to sit unoccupied, the same city where 170,000 people are currently homeless. Now, property markets in cities like Manchester are experiencing the same destructive trends. Despite social housing being in huge demand, their being rented at half of local market rates has meant its production has been decimated; they are just not profitable to property developers and councils do not receive the funding to build and maintain them as they used to. The affordable rent housing that has compensated for social housing’s decline is also far less affordable – being leased at 80% of the already overpriced market rates – ensuring continued growth in gentrification and homelessness.

And here we are now, at the tailend of a pandemic and at the beginning of what will likely be another economic crisis. Once again, there is a commitment to propping up property prices through low interest rates and quantitative easing, exacerbating the problems to which we have become accustomed.

Although, on the horizon, a more insidious development is firmly in view. The largest firms in the financial sector have raised billions of dollars to buy up distressed property in Europe after the pandemic. In fact, buying up distressed real estate – distressed meaning on the verge of foreclosure or in serious need of repair – has become the hottest new investment opportunity. Purchasing swathes of cheap, distressed property in times of economic hardship, with the aim of making some repairs to sell or re-let for much higher prices once the economy settles down, has been Blackstone’s latest trick. The worsening gentrification, homelessness and poverty as a direct consequence is of little concern to Blackstone’s 3.5 billion dollars of profit made by doing this. Now, in the context of economic hardship, Blackstone is targeting Europe with 10 billion dollars to buy such property, while Lloyds banking group is planning to buy 50,000 UK homes with a similar plan in mind.

Worryingly, Desiree explained, this has presented a novel situation where firms like Blackstone or banks like Lloyds could become global corporate landlords, displacing the traditional independent landlord or medium sized real estate company. If this comes to fruition, it is worth considering how quick evictions may become when your protests are met with a soulless investment firm. Or, if the price of housing and rent is determined by a small number of corporations in the financial sector, how likely is it that they will endlessly gentrify the UK until every area has a price range so expensive it drives out every renter who cannot afford to be extorted.

The actions of firms like Blackstone, alongside fiscal policy that intentionally props up property prices has become the playbook for all financial crises. What makes the current crisis unique is that the lockdowns have caused some people in the UK to lose their entire income, while the rest lost a reasonably sized (and sometimes essential) proportion of it. This has left rental debt stacking up and, with the eviction ban now lifted, up to 2 million people are currently living in fear of homelessness.

Should enough rent go unpaid, and homelessness cascades out of control, a wave of small-scale private landlords may foreclose on their homes as they become unable to pay off their mortgages. It will be these distressed properties, likely situated in unprivileged areas, that Blackstone, Lloyds or other corporations will target. It appears we are awaiting a wave of gentrification, rent/housing price growth and homelessnes like never before.

Protections must be given to at-risk tenants to prevent this. However, viewing the overall problem in the longer term, fixing such a multifaceted issue is much more complex. What is clear is that housing must be pulled away from capital markets as much as possible. This means doing away with the incessant need of growth in the housing market. One method of doing so should be increasing the supply of affordable housing through environmentally considerate property development. As written about here and explained to me by Desiree, simply having distressed property be brought into public ownership alone could help to massively increase the UK’s social housing stock and stem the growth in property prices. The regulations on financial services that were expected after 2008 must be made now. Otherwise, we leave ourselves hopelessly prone to another catastrophic economic crisis from the unleashed profiteering of the financial industry.

By allowing a minute part of the population to profit handsomely at the cost of normal working people without repercussions, as occurred in 2008, we continue to forget the mistakes of the past and leave ourselves ever more vulnerable to the consequences of insatiable greed. These changes are not impossible, there is just not enough pressure on governments to regulate financial institutions. Thankfully, there has been a flowering of tenants unions across the UK and US. It is these organisations that people like Desiree and organisations like GMHA are looking to for progress.

In Berlin, local tenant unions lay at the core of setting up the referendum which voted to expropriate the homes owned by corporate landlords to stop the incessant growth in rent prices. If we do not act as those in Berlin have, collectively organising with tenants unions to hold policymakers and financiers to account, we will fail to desist from the incessant focus on maintaining unsustainable growth in the housing market.

These policy decisions and jargon-laden financial services may seem conceptually distant from our daily lives. However, it is the exceedingly profit-first mentality in the backdrop of crises like the pandemic that may further propel us into a society where our landlord is an algorithm coded by J.P Morgan. It is in such a society where the home has lost its value. From a place of family, togetherness and safety; transcended to a reflection of the hollow value that money plays in our society. A reflection which shows how the interests of the vast majority are less than negligible against the very wealthy few.

Underneath our daily reality, a battle is raging. A battle between your average renter/homeowner against corporations in the financial sector over controlling how we live, who lives where and for how much. It is in times of crisis such as now, when getting through the day, the week or the month is the insurmountable challenge, that these cataclysmic changes happen silently to our detriment. As of now, this battle is being lost. It is time we paid attention.

Isaac is a Politics and Philosophy undergraduate at the University of Manchester, a researcher for the Peterloo Institute think tank and a member of Greater Manchester Housing Action.

24 November 2021