By Nigel de Noronha (@deNoronhaNigel)

In the first of series of articles examining the racialised impact of student accommodation in the wards of South Manchester, Nigel de Noronha examines the background to the growth in student population in the area. This work has been gratefully supported by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung and originally appeared on the Greater Manchester Tenants Union's website.

Fallowfield in the 1970s was home to many students. The Owens Park complex accommodated many first-year students whilst the terraced houses opposite provided multi-occupancy housing and profitable investment for landlords who packed them high. With the proportion of young people attending university around 13% at the time and many fewer students from overseas the effects of ghost towns during the holidays were limited to these student ghettoes. With the growth in the proportion of young people attending university and increasing numbers of overseas students there are now around 1.9 million studying full-time. This additional demand for housing in university towns and cities leads to studentification, with significant impacts on the affordability of housing. Research into this has been carried out, It has been the subject of research, particularly in smaller towns and cities. A recent article explores resistance to the financialisation of student housing in Dublin.

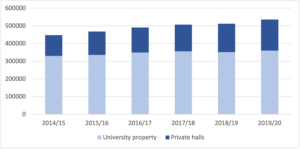

With 63% of students in England leaving an existing home to move into a new one in the 2019/20 year, there were more than a million living in student halls and other rented accommodation. Figure 1 shows how those moving to student halls have become increasingly reliant on private sector accommodation.

Figure 1 – students living in halls from 2014/15 to 2019/20 Source: HESA Statistics

Source: HESA Statistics

More than half a million live in rented accommodation and the number has increased by 10% between 2014/15 and 2019/20. The growth in specialist student accommodation reflects both private halls and group accommodation with enhanced facilities. Investment in buy-to-let properties has also targeted the rising demand for student accommodation. The income from students is significantly more than from working households. The consequence is that new housing built for families is bought by landlords and let to students in popular parts of our university towns and cities. The universities also contribute to increased demand for the available housing by hosting events which feed the demand for AirBnB properties reducing the stock of affordable housing even further..

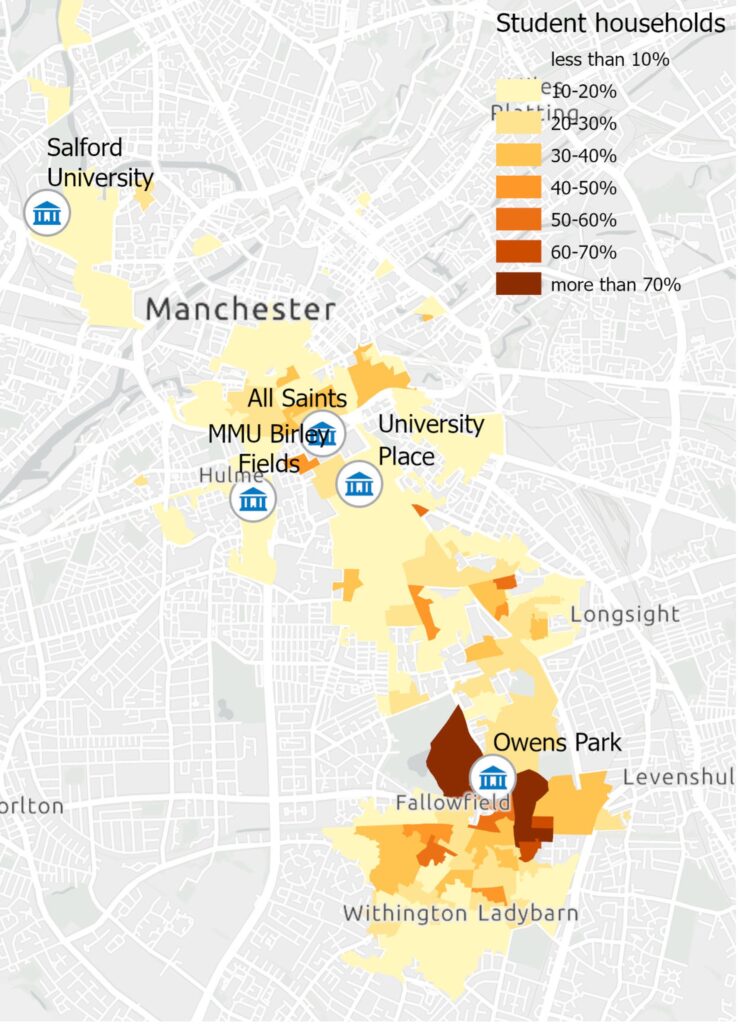

Figure 2 shows how these student households were concentrated in Manchester and Salford based on the 2011 census. They dominated neighbourhoods around Oxford and Wilmslow Road.

Figure 2 – proportion of student households by output area in 2011 Source: Census 2011

Source: Census 2011

Major changes since then include the development of the MMU campus in Hulme and the development of private student flats and new build for investment properties. In 2019/20 there had been a growth in full-time student numbers by 4% to more than 65,000 in Manchester and a growth of 13% to 18,670 in Salford. The official figures are not available for the last two years, but we know that there was a significant increase in both years due to changes in examination arrangements arising from Covid-19. The extent to which accommodation choices reflect different types of students is not clear from the research into studentification. The rise in the financialisation of the market might be expected to contribute to increasing segregation of the student cohorts by citizenship, race and class. The scale of this segregation will be explored once the universities have responded to FOI requests.

The growth in student numbers and the extent to which they are developing distinct neighbourhoods will contribute to the remaking of the neighbourhoods around the universities with the likelihood that students will displace other residents in neighbourhoods such as Hulme, Moss Side and Ardwick together with the potential shift away from university-owned and private housing in Fallowfield. Plans to redevelop the Owens park site with investment from Abu Dhabi to “deliver strong financial returns” were announced in 2014 and planning permission granted in 2015. After they pulled out two years later another deal with Carillion was announced. The following year Carillion went bust.

The housing in the Fallowfield area has suffered from decades of neglect by private landlords whose incentive to invest is limited. Local facilities are geared to the student market and the area is ready for further financialisation as institutional investment seizes the opportunities to redevelop parts of the area.

Nigel de Noronha is a Research Associate at Manchester University, interested in housing, inequality, social justice, race and migration. He is a member of the Greater Manchester Tenants Union.

25 January 2021