By Lily GB (@lilygbrown)

“Thrones are crashing everywhere, and the men of property are secretly trembling” (p. 27)

The ‘manmade’ environment is a colloquialism so embedded in everyday dialogue that we rarely pause to dissect the meaning behind it. While it often refers to ‘human’ made constructs, it is also reflective of the gendered nature of our environment. Our urban structures have historically been constructed by men, for men; throughout history, the female experience of space has been more of an afterthought.

However, the tides started to shift in the 1980s with the ascent of the second-wave feminism. While the movement has been well-traced, discussed, and even contested for its exclusive tendencies; less discussed is the feminist militancy that materialised in the fields of architecture and the urban environment. That is where Making Space: Women and the Man-made Environment, a work first published by the female collective Matrix in 1984, comes in.

The book has recently been republished by Verso with a new and updated foreword, a sign that the issues it addresses continue to bare significance. An offshoot of the 1970s New Architecture Movement (NAM), the Matrix Feminist Design Cooperative was first formed in 1981, offering a socialist feminist approach to architecture and the built environment. Worker cooperatives hold a strong tradition in the sydnicalist history of the British Left, and Matrix were able to fill a void that existed at the crossroads of patriarchy, architecture, and non-hierarchical cooperative practice.

As Katie Lloyd Thomas and Karen Burns inform us, Matrix evolved amid a hotbed a of local activism. In London alone, ‘a 1975 survey estimated that 20,000 squatters were living in council housing’ (p.x). Whilst the housing crisis is so often traced back to the 1980s and the advent of Thatcherism, many people across the UK were facing barriers in and to housing pre-1979, particularly single women and single mothers. In understanding this context, the establishment of Matrix and the publication of Making Space appear both timely and necessary.

Despite the book’s subtitle (Women and the Manmade Environment), it is largely comprised of an examination of the female experience of housing rather than the built environment more generally. Each chapter is taken up by a respective female scholar and/or practitioner, straddling a variety of disciplines from housing to urban design to healthcare provision and reform; many of the authors were also associated with Matrix. They impart their perspective on a variety of different subjects and experiences, offering the reader part history, part social theory and part memoir.

The Opening

The introduction immediately transports us to the present, asking us to ‘consider [our] surroundings’. The ‘home’, so often celebrated as a sphere of freedom and individuality, is a complicated space. Whilst for many it is a domain of retreat and refuge, for others it marks yet another space whereby (unpaid) work is to be performed. This has historically been the case for women, who play an outsized role in the social reproduction of capitalism. Whilst men were historically granted the physical border between the workplace and the home, women have not been afforded the same sentiment of separation. Conversely, however, the home is also a space where women often access higher levels of autonomy. As the book notes, the ‘home’ is a contradiction.

The introduction also tells us that we are not simply about to embark on an account of gender relations, but one of how they intersect with the wider structures of the capitalist economy: “we do not believe that the buildings around us are part of a conspiracy to oppress women. They have developed from other priorities, notably the profit motive” (p.9). The book goes on to unveil the inseparable influences of patriarchy and capitalism on the livelihoods of women and their experiences of the built environment, situating female oppression within political economic structures.

Readers of the work will not be surprised to learn that architecture and its related fields have traditionally been dominated by upper class white men. This immediately produces problems. Housing (at least it used to) forms one of several pillars of welfare provision; and for this to be dictated and determined by a select, detached few will inevitably carry consequences.

As Jane Darke notes in chapter 2, female and/or working-class architects have traditionally been forced to adopt the conscience of middle-class men (p.11). This has implications for the provision of housing and the built environment; housing designed by men has consistently failed to account for the experience of marginalised groups. Not much has changed in contemporary fields of housing and planning; planning consultancies tend to be comprised of university-educated individuals, and largely men.

The impact of ‘representation’ remains a contentious debate. As Dawn Foster illuminates in her antidote to ‘lean in’ culture, Lean Out, more female CEOs certainly is not the answer; such a theory applies to architecture and planning. However, Making Space does not simply demand greater representation, rather it maintains a that a robust feminist movement is ‘indispensable’ to incite any genuine change (p.25).

The book, particularly in Chapter 3, is historically informative, tracing the establishment of the Women’s Housing Subcommittee 1918. Guided by a similar ethos to the Women’s Labour League, both helped pioneer the way for a women’s voice in public services and work, maintaining that women should be at the forefront of housing provision and design. They set out to expose the conditions of working-class women’s lives, visiting estates across the country and producing their findings in 1918. Unsurprisingly, their findings didn’t tempt a genuine change in policymaking, but it did set the tone for future feminist thought in architectural practice.

Despite the importance of the Committee’s work, McFarlane articulates frustration in the fact that whilst the changes proposed would improve the conditions of women in the home – particularly through enhanced physical design – the suggestions reinforced women’s role as domestic servants and confined them to their oppressive livelihoods as housewives propping up the structures of social reproduction.

Communalism – A Panacea?

Chapter X, Roberts’ ‘Private Kitchens, Public Cooking’ also provides a cogent critique of the home and the female existence within it. Advertising between the 1920s-1950s saw ‘pictures abound of women/wives serving meals to their brightly expectant families’ (p.106). Picture Madmen’s Betty Draper serving up a freshly baked pie in an outfit that could neither be defined as either an apron or a dress.

But the reality of the private (home) kitchen in not always a domestic idyll. As Roberts notes, whilst cooking itself might be a pleasurable activity, all that comes with it is hard and often demoralising work. Here we come to the alternative idea of ‘community feeding’. Forming a part of the war effort, Community Feeding (renamed ‘British Restaurants’ for Churchill’s fear that community feeding was an odious suggestion, indicative of ‘communism and the workhouse’ – p.109) adopted a utilitarian approach to domestic chores: ‘simple meals and simple prices’. They essentially acted as community cafes, usually containing women serving hot meals to local residents and families.

Although the state-supported British Restaurants later declined and might not be defined as a ‘revolutionary endeavour’ in women’s liberation, the experiment ‘combined an approach to issues of poverty and malnutrition with an implicit challenge to women’s unpaid labour in the home’ (p.118). Since, community cooking and housing has struggled to find a place within the British psyche. Alongside the home and the family, cooking has been traditionally regarded as a private activity to be performed by women.

However, these experiments in communalism – also evident in the cooperative housing movements and collective rent strikes of the twentieth century – are vital in for any leftist feminist movement, producing a vision of genuine liberation. We can read the book therefore as an educative tool in community organising, situating the female struggle within it. As welfare provision continues to disintegrate and the cost-of-living crises mount, alternative forms of local community activism, predicated on solidarity, will be more expedient than ever.

Public Space

Moving beyond housing, chapter 4 offers an insight into Matrix’s perspectives on public space. In recent years, the gendered nature of public space has become the subject of a great deal of public debate. This debate has centred around the matters of safety and harassment. How our built environment, housing provision and cuts to domestic violence services continue to harm women has been taken up by inspiring movements such as Sisters Uncut.

Matrix’s chapter on public space takes on a slightly different topic. Whilst safety and sexual harassment within public space are considered, the book also examines how planning practice – particularly New Town planning of the mid-twentieth century – constrained the female experience of public space.

New Towns and the ‘neighbourhood units’ contained within them were pitched as spaces convenient for women and their new families (with schools, shops, and public facilities in a short walking distance); however, the reality was a little different. Whilst there might’ve been a ‘benevolence’ (p.40) in reducing travel times, women were confronted with an absence of choice in their day-to-day lives. These new public spaces were built with gendered visions of society in mind; one which confined women to their domestic duties and reduced their mobility, particularly difficult for those unable to afford a car.

Conclusions

Making Space is both a timely and necessary read. Many of the issues it deliberates can still be applied today; some have even intensified. Whilst the feminist movement has consistently fought for a fairer deal in housing and the built environment, the struggles are still very much alive. Women fleeing domestic abuse continue to face challenges in accessing service support or state-funded housing; austerity has profoundly impacted women and mothers; trans women are excluded from housing provision and access to basic services; and migrant women continue to be detained and abused in centres such as Yarl’s Wood.

Whilst the book might be lacking in explicit solutions to these crises, it does not claim to contain all the answers. Rather, in the introduction we are told: “we are not prescribing a solution, we are describing a problem.” It does, however, provide food for thought, particularly on communalism and local organising.

This leaves us with the question of ‘where next?’. As the book suggests, just as in the 1980s, a robust collective movement is required to truly challenge the ingrained systems of private property and patriarchy, and to demand justice through reclaiming now privatized public spaces.

As Harvey illuminates in his 2008 Right to the City, the spatial forms of our cities increasingly consist of ‘fortified fragments, gated communities and privatised public spaces kept under surveillance’. Anna Minton, in Ground Control, explores these urban processes in the context of the UK, whereby post-industrial cities have been commanded by undemocratic governing structures such as Urban Development Corporations, Enterprise Zones and, more recently, Business Improvement Districts (BID).

Ostensibly predicated on notions of ‘safety’ and ‘respect’, these public-private partnership processes have gone no way in enhancing the welfare of women. Rather, they see to it that the built environment is entirely dictated by the profit motive.

In challenging this, we can look to the tenant movements cropping up across all corners of the globe and resisting the tides of gentrification, dispossession, and displacement. At a more local scale, urban struggles led by the likes of Sisters Uncut are, through direct action, demanding justice at the intersections of domestic abuse services, welfare cuts and housing provision – placing genuine liberation at the heart of their demands.

Lily GB is studying Housing and Community Planning at the University of Liverpool. She is a regular contributor to GMHA, and author of recent pamphlet 'The Housing Crisis is a Land Crisis'.

Making Space is available to buy from Verso Books.

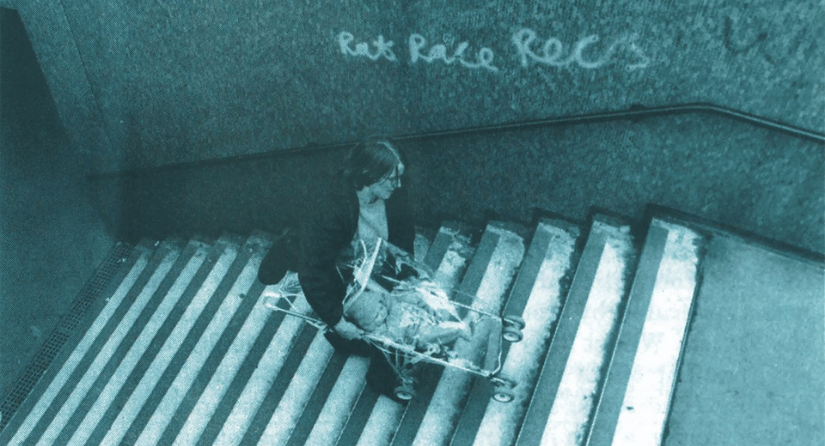

Cover Image: Anne Thorne with son, photographed by Liz Millen, Archway, London. Taken from the cover of Making Space: Women and the Man Made Environment by Matrix

13 June 2022