By Nigel de Noronha (@denoronhanigel)

This contribution to the debate about housing after Covid argues that racial discrimination is a long-standing feature of British housing policy, provides emerging evidence of racial inequalities in debt and future housing expectations, and proposes the grounds for a broad-based campaign to re-assert the right to adequate, affordable housing for all.

Increasing levels of debt, street homelessness and the threat of eviction disproportionately affect marginalised groups. The impacts reflect historical housing policies whose effects have been discriminatory, favouring those with the resources to own property to live in or rent out at the expense of tenants and discriminating against migrants and racial minorities.

Historical racial discrimination in housing and immigration

Racial discrimination has been evident in the housing market for more than a century limiting the choices available to those who migrated from the New Commonwealth and elsewhere after the Second World War, forcing them to either buy houses using mortgage clubs and other collective ways of raising funds or to rent in specific districts of the cities they settled in. The removal of the rent freeze which had been in place since 1939 by the Conservative government in 1957 led to intimidation and illegal eviction to remove tenants and replace with those who would pay higher rents. At the same time politicians from different parts of the country argued for immigration control because of the housing situation in their towns and cities. The housing crisis of the period led to a Royal Commission which failed to publicise the racial dimensions of the situation but did tilt the balance back in favour of tenants through the 1965 Rent Act which provided security of tenure and rent control.

Increasingly restrictive immigration controls reduced primary immigration from the New Commonwealth to a trickle, removed the right of children born in the UK to automatically acquire British citizenship and developed internal border controls for access to education, health and housing. The idea of the property-owning democracy was re-invigorated by the introduction of the Right to Buy council housing at substantial discount in 1980. Since 1980 more than a third of the council housing stock (two and a half million homes) has been bought. Subsequent evidence suggests that many of these homes are now part of the private rented sector (PRS). In 1988 rent controls were removed, tenancy protection was reduced substantially, creating the PRS environment that we now live in. From the 2000s we saw increasingly restrictive immigration controls extended from trials with asylum seekers to all migrants. As immigration controls arising from Brexit begin to kick in those from the EU who used to have the right to live and work in the UK will increasingly be incorporated in these controls. An important thing to recognise here is that the discourse around immigration and the hostility to migrants has been translated to discriminatory practices. Whilst the law says those with specific citizenship statuses do not have the right to housing, officers, local authorities and housing providers have developed local rationales for exclusion and treated some as not entitled because of the way they look or sound.

The right to adequate housing has increasingly been curtailed by the dominance of the housing market. Developers have had the priority to determine what is built and where. They have ignored local housing need, ignored affordable housing agreements they made when planning permission was granted and have built for investment. Their focus was on profit. At the end of 2020 over £200 billion pounds was held in buy-to-let mortgages by individual investors with £35 billion advanced in 2020. This does not include individual investors with cash, properties bought as assets on international exchanges or the growing size of corporate investment. Some of these properties are poorly maintained and overcrowded to maximise profit. The impact of poor-quality private rented housing has affected the wellbeing of marginalised groups in both urban and rural areas.

Housing market interventions as a result of Covid

As a result of Covid, those who own their homes with a mortgage have been able to apply for a six-month mortgage holiday – this includes both homeowners and landlords. There has been a promise of no evictions from rental properties though in a rule change earlier this year evictions of those with more than six months arrears have been allowed and the London Renters Union is currently fighting cases in the courts. The ‘Everyone In’ programme provided accommodation for those who were street homeless in hotel accommodation. Probably the biggest cost has been the Stamp Duty holiday which redistributes money to those who can afford to buy their homes including landlords acquiring buy-to-let houses.

Emerging evidence

Debt

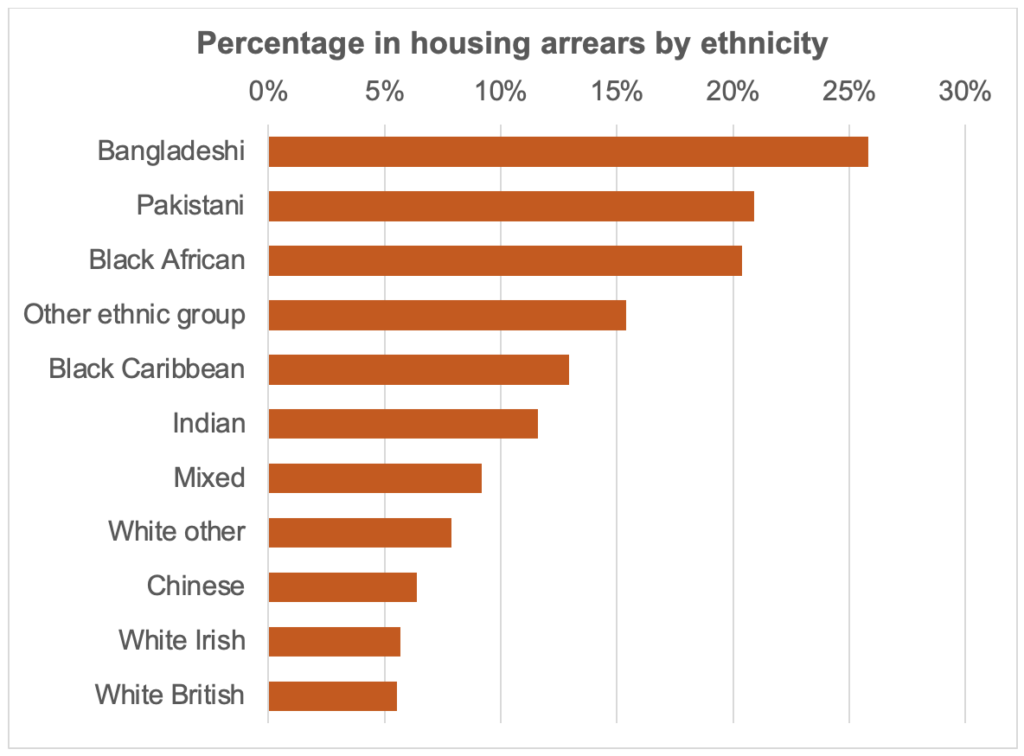

Overall, around 6% of households responding to the Understanding Society survey were in arrears with their housing payments. Those born outside the UK were twice as likely to be in housing arrears. Single parents and other households with dependent children twice as likely and social housing tenants two and a half times as likely to be in housing arrears. Figure 1 shows that the starkest evidence of inequality is by race with a quarter of Bangladeshi people and a fifth of Pakistani and black Africans in housing arrears.

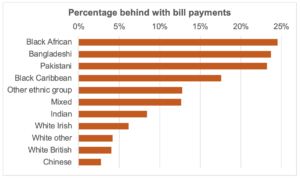

Similar patterns emerge when looking at those behind with bill payments. Around 5% of the respondents were behind with bill payments. In comparison, more than twice as many born outside the UK, 17% of single parents with dependent children, 21% in social housing and 11% of private rented tenants were behind with bill payments. Figure 2 shows that again race has a significant effect with more than 20% of black Africans, Bangladeshis and Pakistanis behind with bill payments.

Intention to move

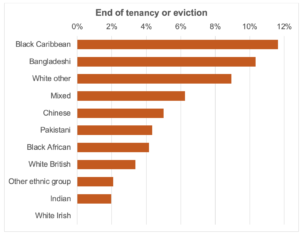

For some households, Covid has provided an incentive to improve their housing situation. Proximity to work and access to leisure opportunities have become less important whilst more space, a garden and access to green spaces have become more important. For other households, reduced income, unemployment, debt and job insecurity are forcing them to move. Over a quarter of respondents to the Understanding Society survey said that they intended to move. The majority of these (66%) were to improve their housing situation, to downsize or to form a new household whilst 30% cited other reasons. The remaining 4% cited the end of their tenancy or eviction. Twice as many lone parents with dependent children and members of other households intended to move because of the end of their tenancy or eviction. Four times as many in the private rented sector and one and a half times as many in social housing also intended to move because of the end of their tenancy or eviction. There was little difference between those born in the UK and those born abroad. Figure 3 shows that black Caribbean, Bangladeshi, White other and mixed ethnic groups were more likely to intend to move because of the end of tenancy or eviction.

Whilst eviction claims reduced significantly across all tenures during the Covid pandemic, there are early signs of increasing claims to the county courts for those in private rented and social housing in the fourth quarter of 2020. There is likely to be an acceleration due to increasing arrears and the lifting of the temporary protections for eviction in May.

Conclusion

Housing policies and the behaviour of the housing market have consistently created structural inequalities. The temporary interventions to address issues raised by Covid have favoured homeowners and landlords more than tenants. They are likely to be followed by an acceleration in evictions affecting those in most need. For those who can make the choice to move to places with gardens and more space, the added incentive of the stamp duty holiday seems likely to lead to significant moves. These may in turn trigger the displacement of existing residents and the reduction of housing choices for their families as market demand increases the prices of suburban and rural housing. For those who cannot afford the choice the spectre of overcrowded, unsafe and insecure accommodation looms large.

The government has demonstrated no evidence of seriously getting to grips with the housing situation in the country, preferring to apply sticking plasters to address perceived issues raised by the stakeholders they listen to rather than considering the international commitments the UK has made to provide adequate housing for all.

The government needs to accept their duty to support the provision of the right to affordable, adequate housing (as agreed under the UN Convention of Social and Economic Rights in 1976). I suggest that the following actions provide the basis for a campaign to secure decent, affordable housing for all.

- Cancel individual debt arising from the Covid pandemic.

- Revise planning legislation to curtail the powers of developers and require them to build to address local housing need and provide adequate affordable housing.

- Introduce regulations in housing markets to protect local communities from being displaced by gentrification.

- Enforce action by landlords to address unsafe conditions in their properties and to apply compulsory purchase orders to those who fail to do so.

Nigel de Noronha is the Assistant Professor at the School of Geography at the University of Nottingham.

23 March 2021