By Carl Makin (@carlmakin)

“When people feel supported by strong relationships, change happens. And when we make collaboration and connection feel simple and easy, people want to join in. Yet our welfare state does not try to connect us one to another.” [1]

Loneliness is a constant and growing social problem, and attention is turning to ways that we can challenge it through new practices in our everyday lives. One potential route is through cohousing, a form of community-led housing which focuses on the provision of self-contained homes clustered around communal space and facilities intended to encourage collaborative living.

Summarising its appeal, Maria Brenton, the UK Cohousing Network’s Senior Cohousing Ambassador opened the Greater Manchester Housing Futures event ‘Cohousing: potential and challenges’ with the above quote from a recent Guardian article. Held on Thursday 21st June, the event was the second in our series on community-led housing, more details of which can be found here. Speaking alongside Maria on the panel were Bill Phelps from Chapeltown Cohousing in Leeds, Housing Future’s researcher Richard Goulding as well as Pam Flynn from Manchester Urban Cohousing and Steve Gosling from Chorlton Cohousing.

As an ‘intentional community’, cohousing requires individual residents to commit to a set of collective values and participate in community activities. The modern cohousing movement was born during the 60s and 70s out of various movements across Denmark and Sweden.[2] The benefits of cohousing are numerous, but perhaps most importantly, it helps to break down the barriers built into current housing models which work against communality, and seeks to address the housing, social and informal care needs of its residents by relying on collective working and inter-generational solidarity.

Here are five things discussed at the event which we believe make the case for the expansion of cohousing in Greater Manchester:

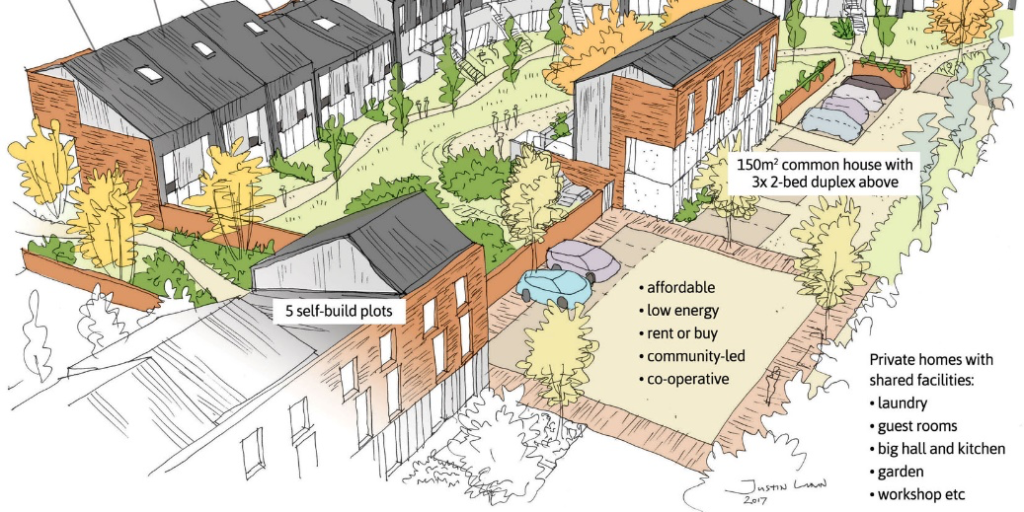

Artist's Impression of the Chapeltown Cohousing scheme

- Housing can, and does, foster loneliness

Loneliness is endemic and blighting modern society. Research by the Jo Cox Loneliness Commission revealed that over 9 million people in the UK (nearly one-fifth of the population) often or always feel lonely.[3] In many ways, our housing system compounds this issue by focussing almost exclusively on self-contained properties with no provision for community space. Deep cuts made to local government funding have led many councils to close community centres and sports facilities, further reducing the available space for people to get together, and entrenching the isolation which exists in our communities.[4]

Community interaction and shared living are built in to the cohousing model. Maria Brenton spoke about her experience with Older Women’s Cohousing in Barnet, a scheme consisting of 25 self-contained flats, 8 of which are let at social rents. Older Women’s Cohousing has a shared common house with a meeting room and kitchen. This ‘hub’ and the large, central communal garden are managed by the residents, who share responsibility for their upkeep and for arranging regular community meals and events intended to bring everyone together. Although cohousing is not a panacea for loneliness, this experience illustrates how it can provide a community infrastructure built on a balance of shared living and privacy which enables and encourages social interaction.

- Sharing communities

Sharing is also implicit in the cohousing model. Shared facilities, shared responsibilities and, to an extent, shared lifestyles help to foster and maintain communities. Beyond this, cohousing also brings the added value of skill sharing. Maria Brenton mentioned the significant amount of upskilling required within Older Women’s Cohousing to ensure that they could deliver on their original vision and to ensure that they had the skills to make the project sustainable in the long term.

The logistics of setting up a cohousing scheme can be very complex and technically detailed, but in doing so residents can develop and share their understanding with future projects. Bill Phelps from Chapeltown Cohousing spoke of their learning curve, which involved working with planners and architects, as well as drawing on government funding, loan stock and community shares to raise the necessary capital for the scheme. As the UK community-led housing movement grows, Housing Futures hopes to contribute to establishing a community-led housing hub for Greater Manchester which will bring existing local expertise and knowledge together in one place. The importance of this was drawn out by the Chapeltown experience, which has relied heavily on support from the Leeds community-led housing hub developed by Leeds Community Homes.

A barbecue held at Older Women’s Co Housing in Barnet

- Caring communities

We often hear about the social care crisis brought about by a systemic lack of investment coupled with an ageing population. Research shows that there is an urgent need for new ways to deliver low-level support and help maintain independence as people grow older.[5] Senior cohousing communities celebrate and support this independence, not by replacing social care, but by preventing the need for social care through an age-balanced membership which can provide low-level support to its residents where necessary.[6] This inter-generational solidarity has been developed in the Older Women’s Cohousing model in Barnet, where a ‘care rota’ swings into action once a member’s everyday needs increase, to provide a structure whereby other residents help to collect prescriptions, pick up groceries and carpool to take members to appointments.

Maria Brenton, drawing on her experience from Older Women’s Cohousing, and Pam Flynn from Manchester Urban Cohousing, both spoke of the need for communities which value older people, meet their needs and give them a voice. Older Women’s Cohousing’s motto, “We shall not be done unto”, sums up perfectly the ability of cohousing to empower residents and meet their needs in a way which respects their autonomy and reduces unnecessary ‘professionalisation’ of care, whilst allowing residents to maintain active, independent lives.[7]

- Environmental benefits

The ability of new environmentally-conscious cohousing communities to design their accommodation can have a significantly positive environmental impact. Many schemes are finished to a high standard of energy-efficiency and attempt to integrate eco-friendly features. LILAC in Leeds was the first residential development to use a sustainably-sourced pre-fabricated ‘Modcell’ straw bale construction.[8] Springhill Cohousing in Gloucestershire, the first cohousing project in Britain, received funding for a photovoltaic roof tile system. Unsurprisingly, research from the US has shown that cohousing schemes use up to 60% less domestic energy.

- Benefits to the wider community

Cohousing is good for society. Its co-productive structure and community focus have the potential to shift power away from developers, who have a tendency to run roughshod over the wishes and needs of residents in favour of profit margins. Cohousing can also produce good quality social and other low-cost housing within mixed-tenure communities where all residents form part of a support network and are all able to voice their views and shape their locality. For example, Barnet’s Older Women’s Cohousing received a £1 million charitable grant which allowed them to provide eight social homes. Chapeltown Cohousing will offer a third of its housing for rent, with a further eight properties offered under shared ownership through a government grant from Homes England (though this comes with many strings attached due to being designed for larger, institutionalised housing associations). All members of the panel spoke of wanting more affordable and preferably social rented homes in their schemes, but found it difficult to ‘make the sums add up’ within the existing funding environment.

As well as the significant benefits of cohousing, the event also engaged with the difficulties experienced in setting up. One tremendous barrier is the length of time from planning to delivery – Older Women’s Cohousing, for example, took around eighteen years to go from initial idea to moving in. Similarly, Chapeltown Cohousing are due to move into their new homes in 2019, nine years after their earliest discussions. Closer to home, Manchester Urban Cohousing have been meeting monthly for five years, where they come together for shared meals and planning, but have yet to iron out the significant issues of where to build and how to pay for it.

Housing Futures’ research and the event discussions indicate the urgent need for joined-up thinking at a local and national level to enable these schemes to get off the ground. Whilst the Government’s £300 million Community Housing Fund[9] is a welcome start, we need a real infrastructure here in Greater Manchester to support groups from planning to delivery.

4 July 2018