By Abi O'Connor (@abioconnor_)

The Conservative party takeover of Liverpool City Council represents a perfect storm in which corporate powers are able to trial new forms of urban governance which are vacant of democratic representation and wholly unaccountable to the people of the city. The possibility of these even further mechanisms of privatisation reveals the potential for further capital extraction from urban localities, and the working class communities within them.

Whilst the current crisis faced in Liverpool has gained attention in recent months, the corporate takeover of the city has much deeper roots. It has long been ripe for specific forms of capital extraction, realised most acutely under austerity, through what geographer Neil Smith terms the ‘rent gap’[1]. Put simply, the ‘rent gap’ theory refers to the difference between the actual rent paid for a piece of land and the potential value which could be collected if the land were put to ‘higher’ use, offering an economic explanation of gentrification.

So, in Liverpool, whilst house prices rose exponentially post-2008 financial crash, the city’s land and property values remained low, therein offering the highest possible rental yields outside of London. This saw private developers and landlords flock to the city to take advantage of the continuing crisis for residents. The so-called socialist utopia has become a playground for global conglomerates and private property tycoons to turn their first million (and later billion[2]).

Despite establishing a first of its kind land commission in 2020, celebrated widely for its focus on community wealth building[3], Liverpool remains a city defined by corporate landlordism which overwhelmingly legitimises and prioritises private financial gain. This developer-led model of regeneration has been favoured as a means of “saving” the city from economic stagnation. This argument relies on the myth of trickle-down economics and negates the politics of urban restructuring. This model ultimately exists to justify top-down market-led control of cities which have overwhelmingly experienced decline[4].

Business leaders continually lambast the local authority for being hostile to incoming investors[5], claiming the Labour administration are causing a mass corporate exodus and must do more to entice private business to Merseyside. Criticism of the City Council’s mismanagement is not unwarranted in many areas, but the extent to which proponents of a market-led recovery have the best interests of the city’s residents at heart should be critically assessed. For example, relentless focus on the desperation for inward investment at any cost has seen one of Britain’s most prolific property owners, Peel Holdings, gain an increasingly significant grasp on Liverpool’s assets. And that of the North West, and Britain, more broadly, including significant stake in Manchester, Newcastle and across Scotland[6].

Image 1: ‘Peel in the Northern Powerhouse’: Map detailing Peel’s ownership as of 2016. [Update needed as land acquisition grown exponentially]

Peel’s ownership of Liverpool is emblematic of the power – and danger – of speculative land-grabs. And recent changes to the city’s governance risk placing more control in their hands.

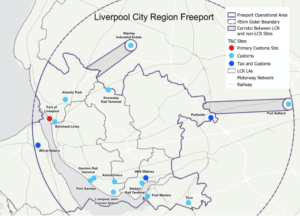

The Port of Liverpool and the Freeport agenda

The Port of Liverpool is Britain’s leading transatlantic port handling 45% of trade from the US, and Peel cite their owner-led investment as pivotal to the Liverpool City Region securing one of eight English Freeport bids in 2021[7]. Previously a Special Enterprise Zone, the area benefits from reduced regulations, tax concessions and infrastructure incentives designed to attract investment. Yet, as Peel owns both Liverpool and the Wirral’s coastlines, they disproportionately profit from these arrangements, with little tangible benefits for the city’s people.

Image 2: Map of Liverpool City Region Freeport, one of 8 “successful bidders in the English Freeports Competition”[8]

The image below shows the, until recently, disused North Docks which promised to be part of their infamous ‘Liverpool Waters’ development programme, which has promised to bring “life back to Liverpool’s historic docklands”[9]. Instead, this space is sublet as storage, fenced off from the city’s residents and surrounded by security.

Image 3: Peel owned land: now filled-in Trafalgar and Victoria North Docks, left part-derelict, part leased out for storage[10]

Britain’s latest Prime Minister, Liz Truss, is an advocate for “full-fat freeports”[11]. Her leadership will undoubtedly see an increased focus on new mechanisms with which to (re)distribute wealth upwards, something she unashamedly committed to during her campaign. Shanker Singham, one of Truss’ closest advisors and the so called ‘brains of Brexit’, and has for years advocated for geographic zones with “regulatory autonomy from their host governments” based on the principles of “property rights protections”, “competitive markets” and “open trading environments”[12].

These economic freedoms that Liverpool will supposedly experience as a Freeport are framed as creating new opportunities, but private companies becoming omnipotent entities is gravely concerning. Research shows decreased employment rights and poor working conditions go hand in hand with the deregulated economic zones[13]. Unite union members at Peel’s Port of Liverpool are undertaking 2-weeks of industrial action over real-term pay cuts in September 2022[14]. These struggles are not detached from issues of undemocratic urban governance.

The acceleration of this anti-democratic developer model is deeply problematic, and is indicative of the Conservative party's will to privatise our very existence, and dispossess everyone but a small elite of assets, rights and opportunities. Beyond Peel swallowing up Liverpool’s waterfront, Hong Kong’s most lucrative billionaire is now turning over millions as the landlord of Liverpool Council’s supposedly ‘worthless’ housing[15], whilst swathes of land have been sold for minute nominal fees to self-made Scouse billionaire Elliot Lawless. Or, they are leased on long-term contracts by the Council, the rent on which goes unpaid[16] – marking a distinct departure from the accountability expected of working class tenants.

Property Led ‘Regeneration’

Liverpool City Council’s penchant for offering financially lucrative deals to private developers is consistent with Manchester’s current form of urban governance. As research by Goulding, Leaver & Silver evidences, Manchester has been sold at pace (and low value) to Abu Dhabi’s elite[17]. Like in Liverpool, these processes have occurred under Labour controlled local governments and at the expense of public ownership. This is a flavour of what is to come, as developer-led regeneration becomes the only form of change.

On top of this, and already vulnerable to state-led displacement, Liverpool’s communities face further precarity owing to the City Council’s embroilment with corruption. December 2020 saw Liverpool’s incumbent Mayor Joe Anderson arrested (and since released on bail), relating to underhand deals in land, property and regeneration.

The fallout of these revelations prompted the Caller Report, which cited an institutional culture of intimidation and inadequate management[18]. This served as justification for Conservative appointed Commissioners being brought into Liverpool in May 2021 to have oversight of key council operations. Originally a temporary measure to oversee management of property, regeneration and highways departments, in August 2022 the Commissioners’ control was extended to all aspects of City Council financial and governance affairs[19].

To bolster external control of Liverpool’s council, and combat further failures in this local political experiment, a strategic advisory panel has been formed which includes Metro Mayor Steve Rotheram and Sir Howard Berstein. Until 2017, Berstein was Manchester Council’s chief executive who oversaw the wholesale privatisation of the city via land and property purchasing. An individual who reproduced archaic tropes to oppose the building of social housing, declaring that creating “successful cities” is “really about how you attract people who have money”[20]. If the Tory takeover of Liverpool’s City Council was not enough to convince us that this power-grab will ensure diminished rights to the city, Berstein’s appointment certainly does.

Liverpool’s already depleted democratic governance is a concern for all residents, who are now at the mercy of unelected individuals. Some of whom have vested interests which are antithetical to equality in the city. For example, one commissioner (paid almost £1,200 a day to establish best value for the public purse) failed to declare that she was a Director of Mulbury Homes Ltd[21], a development company that has strong ties to Liverpool. In February 2022 they went into administration, making hundreds of workers redundant and again raising questions of the suitability of those holding power over land and housing.

Charter Cities

Creeping up in the shadows of the current chaos faced in Liverpool, a new articulation of anti-democratic corporate control is emerging: Charter Cities. A relatively new phenomenon to be considered in Britain, Charter Cities represent a fresh assault on our rights to urban space. One which is wholly compatible with the current model rolled out in Liverpool.

At their very core, Charter Cities enable a private entity to hold urban space in a stranglehold. They are privately owned and privately governed cities, accountable to no one but themselves, termed by scholars as a “private micro state”[22]. Hailing from the United States, this form of governance is unsurprisingly backed by billionaire hedge fund managers who dream of a revanchist city[23], absent of equality, defined by profit accumulation and exploitation by any feasible means. Simultaneously, they maintain the ability to erode all forms of social, economic and political security as they have the power to create new legal frameworks[24].

Charter Cities are therefore predatory by nature, operating as a “neo-colonial, razor-wired port of convenience”[25], which propagate state violence through modern slavery and institutionalised poverty[26], as seen in Honduras[27]. They exist to create even more inequitable landscapes across the globe and make visible how deeply entrenched neoliberalism is in our everyday lives.

Whilst the intervention into Liverpool’s governance and Freeports do not equate to Charter Cities, they have laid the groundwork for the rights of private capital to usurp those of the city more broadly. This, coupled with the knowledge that Charter Cities are a policy option being considered by large sections of the right, indicates that we should be deeply concerned about – and preparing to resist – these evolving forms of financialization.

The possibility of this model becoming a reality reveals the fictitious nature of democratic urban governance today. Intercepting these seismic shifts is time sensitive. Liverpool’s landscape of a failing public and private sector has ensured it is teed up as the ideal place to trial Charter City governance. This has occurred simultaneously to the persistent retrenchment of our rights to the city. Yet, we are currently failing to attend to this crisis with urgency. Collectively speaking, if we do not emphasise the implications of this issue and the ways in which new forms of urban financialisation are built on the foundation of existing struggles amongst workers and communities, then we risk sleepwalking into disaster. It is the responsibility of the left, broadly speaking, to robustly scrutinise these approaching shifts and develop mechanisms with which to confront them.

[1] Neil Smith. ‘Gentrification & the Rent Gap’. AAG. (Sept 1987) pp. 462-465

[2] Tom Houghton. ‘Who is Elliot Lawless? The Scouser changing the face of Liverpool’. Liverpool Echo. (27 July 2019)

[3] Isaac Stanley. ‘Land Commission’. CLES: the national organisation for local economies. (6 July 2021).

[4] David Whyte. ‘The mythology of business’, Centre for Labour & Social Studies. (July 2015)

[5] Tony McDonough. ‘Liverpool has gone backwards’. Liverpool Business News. (19 July 2022)

[6] Peel Ports Group. ‘Our ports’. (2022)

[7] David Huck. ‘Port of Liverpool is gateway for region’s freeport success’. Peel Ports Group. (April 2022)

[8] Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities. ‘Freeports’. GOV.UK. (October 2021)

[9] Liverpool Waters. ‘A Place to Invest’. Peel L&P. (2022)

[10] Abi O’Connor. Photograph taken of Peel owned north docks. (December 2019)

[11] Dominic McGrath. ‘Liz Truss promises ‘full-fat freeports’’. The Independent (25 July 2022)

[12] Shanker Singham. Interview on Enterprise Cities. SeaSteading. (20 March 2015)

[13] Ebenezer Nickson Neequaye, Dechun Huang, Nelson Amowine, Stella Fynn. ‘Empirical analysis of the economic impacts of free ports and their challenges to Ghana’. Journal of Social Sciences. 06 (04). pp 180-196 (2018)

[14] Unite the Union. ‘September Liverpool docks strikes to go ahead after ‘pay cut dressed up a rise’’. Unite Press Release. (Sept 2022)

[15] The Liverpool Post Weekly Briefing. ‘How did homes deemed ‘worthless’ by the council end up in the hands of a Hong Kong billionaire?’. The Post. (15 August 2022).

[16] Tom Duffy. ‘Fury after Lawless misses 30 months of rent payment worth £245k’. Liverpool Echo. (28 August 2022)

[17]Richard Goulding, Adam Leaver & Jonathan Silver. ‘Manchester Offshored: A Public Interest Report on the Manchester Life Partnership Between Manchester City Council and The Abu Dhabi United Group’. Goulding, Richard and Leaver, Adam and Silver, Jonathan, Manchester Offshored: A Public Interest Report on the Manchester Life Partnership Between Manchester City Council and The Abu Dhabi United Group (July 20, 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4168229 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4168229

[18] Max Caller. ‘Liverpool City Council Best Value Inspection’. GOV.UK. (March 2021)

[19] Liam Thorp. ‘Government taking over all finance and governance powers at Liverpool Council’. Liverpool Echo. (19 August 2022)

[20] John Harris. ‘Sir Howard Bernstein on reinventing Manchester: ‘Remarkable things have been achieved’. The Guardian. (18 April 2017)

[21]Companies House. ‘Deborah Ann McLaughlin personal appointment’. GOV.UK. (2022)

[22]Lin Cao. ‘Charter Cities’. Symposium: Rights Protection in International Criminal Law and Beyond. (2019). 27 (3). pp717

[23] Gordon MacLeod. ‘From Urban Entrepreneurialism to a “Revanchist City”?On the Spatial Injustices of Glasgow’s Renaissance’. Antipode. (2002) 34(3) pp602-624

[24] Cao pp717

[25] Ibid. p734

[26] Rahul Sagar. ‘Are Charter Cities Legitimate’. The Journal of Political Philosophy. (2016) 24 (4) pp509-529

[27] Arthur Phillips. ‘Charter Cities in Honduras?’ OpenDemocracy. (7 January 2014)

Abi O’Connor is a final-year doctoral candidate in sociology at the University of Liverpool. Her research focuses on the extraction of economic capital from devalued land and housing markets, and explores how territorial stigmatisation impacts these processes. Through the course of her fieldwork, the messiness of Liverpool’s urban political economy became increasingly apparent, with issues including the politics of authenticity, class and corruption becoming central to the city’s story. Twitter: @abioconnor_

13 September 2022