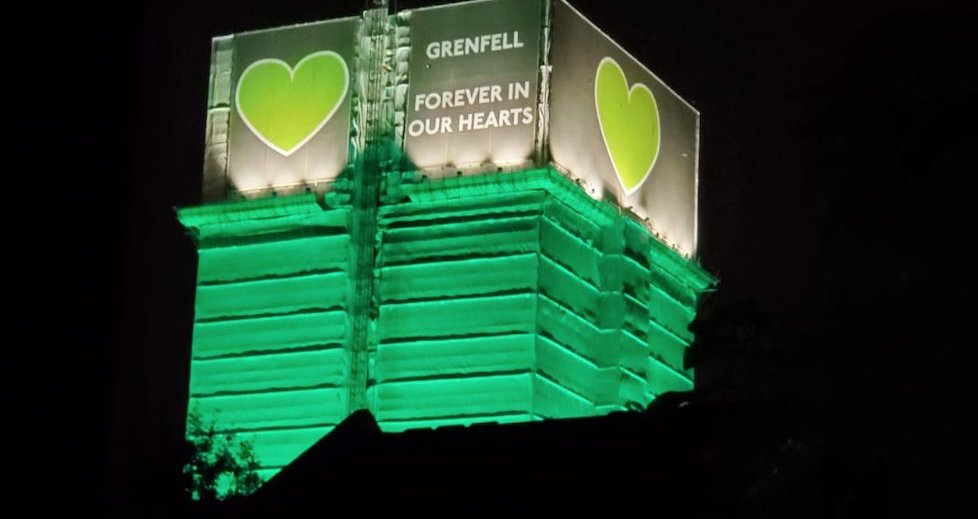

By Stuart Hodkinson (@stuhodkinson) and Phil Murphy (@MancCommunities)

Three years ago, at around 12.50am on 14 June 2017, a small kitchen fire started in a flat on the fourth floor of Grenfell Tower, a 24-storey public housing block of flats on the Lancaster West estate in North Kensington, London. The fire began from an electrical fault in a Whirlpool fridge freezer (a corporate manslaughter tale for another day). It should have posed no problem to the first firefighters on the scene. Grenfell, like most post-war high-rises, was made of reinforced concrete and had been designed to temporarily contain fires within separate flats, known as ‘compartmentalisation’. But this fire did not behave as expected, quickly breaking out of the kitchen window and rapidly climbing up the Tower’s east face until the entire building became a towering inferno.

Grenfell was the deadliest peacetime residential fire for over 800 years, killing 72 people, rendering 201 households homeless, and devastating an entire community. As the #BlackLivesMatter movement resurges worldwide, it is also important to remember that the vast majority of those who died were from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic backgrounds. Survivors believe structural racism played a major role in producing their dangerous housing conditions and in the callous post-disaster response by the state that failed to adequately rehouse people. Seven families made homeless that night are still living in temporary accommodation. And yet, three years after this heinous crime was committed, no prosecutions have been brought against any public officials or the companies that profited from the tower’s deadly refurbishment — Rydon, Arconic, Celotex, Artelia, Harley Facades, Studio E, Exova Warringtonfire, Max Fordham, JS Wright & Co, CEP Architectural Facades Ltd, and Kingspan.

As we remember why Grenfell happened and why so many people died, the need to keep fighting for the living and future generations is more urgent than ever because large parts of the broken regulatory system that produced Grenfell remain in place. In this article, we pay particular attention to the ‘stay put’ policy that played such a decisive role in the high death toll at Grenfell and remains the default instruction to residents living in high-rise blocks in the event of a fire. We conclude that the post-disaster actions of government and industry so far come nowhere close to preventing the next Grenfell from happening.

The public inquiry so far: understanding why so many people died at Grenfell

Prior to Grenfell, the highest recorded death toll from a major tower block fire in the UK was six — at Lakanal House, Southwark, in 2009. So why did so many people die at Grenfell? Despite its many documented shortcomings, the Phase 1 Report of the ongoing public inquiry into the Grenfell fire, led by the retired judge, Sir Martin Moore-Bick, has provided two important answers: the first relates to catastrophic failures in the building’s ability to resist the spread of fire and toxic smoke following its £9 million refurbishment between 2014 and 2016 by Rydon Maintenance Ltd; and the second lies in institutional failings by the local authority building owner, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, its tenant management body, KCTMO, and the London Fire Brigade (LFB) — not the individual firefighters, who were exonerated — which prevented many residents from evacuating to safety. While the LFB should be held accountable for its role, we suggest responsibility for the failure to evacuate residents lies elsewhere.

With great technical detail, the inquiry could not be clearer in its initial findings that “the design of the refurbishment, the choice of materials and the manner of construction allowed an ordinary kitchen fire to escape into the cladding with disastrous consequences”. Of critical significance was the presence of Aluminium Composite Material (ACM) rainscreen cladding panels with highly combustible polyethylene cores, and polyisocyanurate (PIR) and phenolic foam insulation boards behind the ACM panels. Experts found that the cladding and insulation provided a fuel load equivalent of 32,000 litres of petrol and the fire’s spread was facilitated by window and air vent assemblies that provided the fuel and the route for fire to travel rapidly from an internal room to the insulation and cladding, where it found cavities which acted like chimneys. The insulation boards used on Grenfell Tower — and probably present in millions of homes across the UK — released large quantities of carbon monoxide and cyanide gases as they burned. Detailed evidence presented to the inquiry by Professor David Purser, inhalation toxicologist and fire scientist, suggests that the majority of the 72 deaths were caused by the “inhalation of asphyxiant gases”.

Let us now remember that in order to save £300,000, a less flammable zinc-based cladding product originally chosen for Grenfell was replaced at the behest of RBKC in favour of this cheaper and far more incendiary substitute. Retrospective testing found the ACM cladding failed to meet the governments ‘A’ rating safety standards and by the time it had been installed as a cassette system, some of the materials were as low as ‘E’ classification. As an industry source told a BBC investigation, “you wouldn’t put E on a dog kennel”.

Alongside the cladding, the public inquiry found that poor quality design, specification, workmanship and materials across the refurbishment project fatally compromised the building’s ability to resist the spread of fire and smoke travel — a critical layer of fire protection inherent to the original structure. While the intensity of the heat — which reached temperatures of 2000℃ — inevitably caused window glass to break, fire and smoke spread was helped by the use of uPVC window frames and extractor fans that melted at low temperatures, surrounded by flammable spray foam and a thin flammable membrane but without cavity barriers to prevent fire spread. This provided the means for the fire to spread outward from the kitchen in the originating flat. Tests conducted on front doors that were fitted to many of the flats in 2011 and survived the fire intact found that they resisted fire for just 15 of the legal 30 minute minimum, allowing smoke and fire to spread inside the building. On the night of the fire, evacuation efforts of residents and the LFB were hampered by other failures to the smoke ventilation system, the emergency lighting in the stairwell and the lift — all as a result of the 2014-16 refurbishment.

But the high death toll was not simply down to the botched refurbishment. Much — in our view, too much — of the Phase 1 report is focused on criticising the LFB’s senior leadership for failures in planning and preparation for fires in high-rise buildings following the lessons of Lakanal House in 2009, and in how it managed the incident on the ground and in the control room. The Inquiry found that the incident commanders and fire fighters present that night had received no specific training in the particular dangers associated with combustible cladding or how to organise an evacuation; there was no contingency plan for the evacuation of Grenfell Tower; and the LFB’s operational risk database contained almost no information of any use about Grenfell to an incident commander called to a fire. This was compounded by the failings of RBKC and KCTMO who, despite repeated requests by the LFB on the night for a list of residents — including details of vulnerable residents that couldn’t self evacuate — and plans of the building, failed to provide this information until 8am. It was subsequently found to be “15 years out of date”. These factors contributed to the LFB’s decision not to attempt to evacuate the building until 2.47am, nearly an hour and a half after the compartmentation was breached. Many of the 227 people who survived did so by ignoring the LFB’s instruction to ‘stay put’ and self-evacuating instead.

The failure to evacuate the building so long after stay put became unviable undoubtedly cost lives. Yet the inquiry is wrong to place all the blame on the fire brigade for this — its role was and remains to rescue people from fires, not to plan an evacuation strategy for every building it could possibly be called out to. What is missing from the public inquiry to date is an historical understanding of the role of building owners and landlords in making ‘stay put’ such an article of faith in discharging their legal duties towards the safety of residents living in their homes and why alternative strategies, that protect escape routes, as used in some brigades, were not national policy at the time of the Grenfell fire.

Before Grenfell: systemic failures and institutional indifference

What happened at Grenfell Tower is undoubtedly complex, perhaps explaining why the public inquiry has so far focused on establishing the ‘facts’ of what happened on the night of 14 June 2017. Although the government has declared the Grenfell cladding to be unlawful, the public inquiry chair, Sir Martin Moore-Bick, has so far only concluded that the refurbishment works to the external walls of the building were unlawful by leaving them unable to adequately resist the spread of fire. Phase 2 of the Inquiry — currently paused due to the Coronavirus pandemic but restarting in July — will seek to understand how this happened over the next couple of years although it is likely to remain focused on non-compliance with the law, rather than exploring the culpability of previous governments and their policies.

Nevertheless, there is already plenty of evidence pointing to the root causes of the disaster: namely the systemic policy and regulatory failures of central and local government, and the institutional indifference to the safety of residents exhibited by the housing construction and landlord sectors. This can be encapsulated in two unbelievable yet true facts about Grenfell: first, that despite the presence of so many design and construction failures, the deadly refurbishment passed all 16 known building control inspections by the local authority between 2014 and 2016; and second, residents repeatedly raised concerns about fire safety and the standards of works dating back to 2011 to RBKC, KCTMO, Rydon and other bodies that were routinely ignored and even aggressively shut down with threats of legal action. This prompted the chilling prediction in November 2016 by residents who were members of the Grenfell Action Group:

It is a truly terrifying thought, but the Grenfell Action Group firmly believe that only a catastrophic event will expose the ineptitude and incompetence of our landlord, the KCTMO, and bring an end to the dangerous living conditions and neglect of health and safety legislation that they inflict upon their tenants and leaseholders…. It is our conviction that a serious fire … is the most likely reason that those who wield power at the KCTMO will be found out and brought to justice!

Yet the Grenfell disaster was not simply foretold by its own occupants. A series of deadly cladding fires dating back to the mid-1970s generated the same demand by campaigners for much stronger building regulations. While devolved governments in Scotland and Wales took some steps prior to Grenfell to improve building safety, the UK government in England consistently refused to listen and act. Why? Because since the neoliberal victory of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, successive governments of all political persuasions (Conservative, Labour and Coalition) have been ideologically committed to rolling back state provision and social protections to boost capitalist profitability through privatisation, outsourcing, deregulation, self-regulation and more recently, austerity. These policies fundamentally weakened both the safety standards governing construction and building occupation, and their enforcement at the time of the Grenfell fire.

This neoliberal-corporate complex explains why, in addition to Grenfell Tower, an estimated 2000 high-rise buildings (18 metres or taller) housing at least half a million people are at serious risk from different types of combustible cladding; and once buildings under 18 metres are included, the real figure could be anywhere between 11,000 and 100,000. Research by Inside Housing traces this particular story back to the 1997 privatisation of the Building Research Establishment (BRE) that turned a public safety body testing, certifying and approving building products and systems into a highly commercialised actor embedded in the private building and materials industry that derived a significant amount of its annual income from testing and certifying products of the insulation and cladding industry.

In 2006, the privatised BRE ran a closed-door industry consultation on proposed new energy efficiency regulations designed to fulfil the UK’s promise to reduce carbon dioxide emissions under the 1997 Kyoto Agreement. With government, developers and landlords all baulking at the enormous cost of insulating millions of existing homes, this corporate lobbying saw the building regulations subtly changed. A previous outright ban on combustible cladding and insulation in buildings over 18 metres high was watered down and an alternative legal route created through which combinations of cheaper combustible materials previously outlawed could be used. In 2014, the Building Control Alliance (BCA), which represents building control officials, agreed to formalise the approval of this cladding without it even being fire-tested as a system, through the use of ‘desktop study reports’ based on existing test data supplied by government-approved testing bodies, including BRE. It is worth noting that in April 2016, a BRE report into high-rise cladding fires recommended no changes to the existing building regulations.

Putting profit before safety also explains why Grenfell Tower and the vast majority of these high-rise buildings encased in flammable cladding do not have sprinkler systems fitted. Sprinklers have almost eliminated fire deaths where fitted and reduced damage to health and property. Yet in England, sprinklers have only been required in buildings taller than 30m and constructed since 2007 with no requirement for retroactive installation unless a fundamental change is made to the structure or use of the building. This is despite the All-Party Parliamentary Fire Safety and Rescue Group of MPs warning four consecutive government ministers about the need for urgent action following the deadly 2009 Lakanal House fire in Southwark. The Coalition Government’s response in 2014, was that it was “the responsibility of the fire industry, rather than the Government, to market fire sprinkler systems effectively and to encourage their wider installation”. The UK is also one of a very small number of countries worldwide that has built residential high-rise blocks with only a single means of escape stairs and thus residents live with the ever present prospect of being trapped by fire or smoke with no alternative means of escape.

The clear failures in how KCTMO managed fire safety at Grenfell Tower before, during and after the refurbishment are themselves a product of flawed changes to regulations governing the management of common parts of rented housing introduced under the 2005 Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order (RRFSO). The RRFSO brought in a self-regulated system in which building owners, landlords or managing agents were made legally responsible for assessing and mitigating fire risks to people in the building — including the possible need for evacuation strategies — whilst at the same time placed under no specific obligation to conduct fire risk assessments in a given time period and free to employ their own unregulated fire risk assessors. The Fire Protection Association reported in 2018 that nearly two-thirds — 500 — of the 800 fire risk assessors operating in the UK were not registered with accredited bodies.

Fire safety failings have been exacerbated by austerity with huge cuts to stand-alone fire and rescue authorities: since 2010-11, over 9,000 fire and rescue service jobs in England have been lost — a 20 per cent cut. As a result, in the five years up to 2017, the number of fire safety inspections in tower blocks fell by 25 per cent. The impact closer to home is worrying: an FOI request to the fire and rescue service in 2018 revealed that of 489 Greater Manchester tower blocks “75% were deemed not to have met safety standards”. However, fire service inspections are not normally very rigorous examinations of a building’s fire-resistant structure. We should therefore be terrified by the courageous public admission last year by Hyde Housing that all 86 of its tower blocks over 18 metres failed a Type 4 fire risk assessment — the most intrusive kind — with problems ranging from “serious and widespread compartmentation breaches”, “flammable and/or sub-standard cladding installations” and “missing or poorly installed fire stopping and fire breaks”.

Then there is the vexed issue of ‘stay put’ versus ‘evacuation’. The principle of stay put has been at the heart of England’s building regulations for purpose-built blocks of flats for decades. It originally rested on the simple idea that compartmentalisation will contain fire and smoke within the flat of origin adequately and for long enough to enable residents in other flats to safely evacuate. The building code guide that applied to high rise blocks built in the 1960s and 1970s was called CP3. Contrary to what many commentators are assuming, the strategy in those guides was to protect the stairs for use by evacuating residents at any time, including during a fire: “occupants of any dwelling may seek to leave the building therefore, provision should be made for them to do so, unaided, using adequately protected escape routes” [CP3 1971].

Yet stay put rested on critical assumptions about the integrity of fire resistance in post-war high-rise blocks made from reinforced concrete and local fire-fighting capacity. The most important of these are that the original compartmentalisation was sound and has not subsequently been breached by building works, and that there is only one fire in one compartment at any one time or fire-fighting becomes extremely difficult. In the years prior to Grenfell — particularly since the mid-2000s — many of the facts on the ground that once made those assumptions logical and reliable began to change in a deregulated environment. These include the industrial scale of combustible cladding and other highly toxic synthetic materials, shoddy design and construction work, poor maintenance management, and the sheer quantity of plastics being used inside both existing and new blocks.

One significant outcome, as related in official fire incident data, is the frequency of fires in flats that affect multiple floors, a strong indicator of catastrophic compartmentation failure. Over the last 8 years this has happened on average every three weeks in blocks over four storeys. One of the most significant compartmentation failures took place at the 2009 Lakanal House fire in Southwark that killed six people. Just as at Grenfell, combustible cladding, dangerous refurbishment work, the absence of sprinklers, and poor fire risk management by the local authority landlord were all present. Crucially, so too was the advice of the LFB during the fire to stay put that contributed to the fatalities; those who survived did so by self-evacuating. Lakanal exposed the reality that building alterations and mis-management had rendered stay put ineffective and that there was no strategy in place by the local authority landlord to evacuate the building in the event of a compartmentation failure.

Remarkably, the response to Lakanal by local government, national fire chiefs, and the landlord sector — both social and private — was not to learn the (undoubtedly expensive) fire safety lessons from the disaster, but instead to find a way of pretending it never happened. The result was the 2011 Local Government Association’s (LGA) Guide to Fire Safety in Purpose Built Flats, written for the LGA by private fire safety consultants, C.S Todd and Associates Ltd, in consultation with the Chief Fire Officers Association and a range of mostly landlord representative bodies (including the National Federation of ALMOs, the National Housing Federation, the Chartered Institute of Housing, the (now dissolved) Tenants Services Authority, the National Landlords Association, and the Residential Landlords Association), many of whom purporting to represent residents’ views without consulting any living in high-rise buildings. The LGA guide’s purpose appears to have been to preempt any recommendations from the Lakanal coroner’s inquest and avoid the inconvenience of having to devise evacuation strategies for high-rise dwellers. It did this by downplaying the risks of fires and need for evacuations in high-rise buildings, dismissing the need for central fire alarms and sprinkler systems, and insisting that stay put was in fact “an evacuation strategy” that should always be the default approach with residents expected to remain in their homes unless directed to leave by the fire and rescue service. The ethos of this ‘fire safety’ guide can be summed in the following extract:

Some enforcing authorities and fire risk assessors have been adopting a precautionary approach whereby, unless it can be proven that the standard of construction is adequate for ‘stay put’, the assumption should be that it is not. As a consequence, simultaneous evacuation has sometimes been adopted, and fire alarm systems fitted retrospectively, in blocks of flats designed to support a ‘stay put’ strategy.

This is considered unduly pessimistic... [and] is not justified by experience or statistical evidence from fires in blocks of flats... [or] the principles of fire risk assessment... Accordingly, proposals of fire risk assessors, and requirements of enforcing authorities, based on a precautionary approach (eg abandonment of a ‘stay put’ policy simply because of difficulties in verifying compartmentation), should be questioned (p.28).

The significance of the 2011 LGA guide cannot be understated. The 192 page document asserted itself as the high-rise fire safety bible for landlords, fire risk assessors, and enforcement officers in fire and rescue authorities — including the LFB — offering the definitive interpretation of best practice fire risk assessment and the legal requirements for ensuring fire safety on housing providers and enforcing authorities. The LGA guide contributed significantly toward the entrenchment of ‘stay put’ as the only evacuation strategy pursued by building owners, landlords, their fire risk assessors, and by the fire and rescue authorities who were instructed to follow its advice. It is the principal reason why, in 2017, Grenfell Tower, like virtually every high-rise building across the country, had a ‘stay put’ policy in the event of a fire. Yet, ‘stay put’ is not an evacuation strategy. We are in no doubt that if there had been a genuine and functional ‘evacuation strategy’ in place on the night of 14 June 2017 intended to get people safely outside of the building, every single person who died would have instead reached fresh air. Crucially, the failure to create an adequate evacuation strategy lies foremost with the landlord sector and the 2011 LGA guide, not with the LFB or any fire brigade.

What has changed since Grenfell?

In the immediate aftermath of the Grenfell disaster, then Prime Minister Theresa May promised that her government would learn the lessons and take action. Some things have changed for the better. Building regulations were amended from 21 December 2018 to ban the use of “some” but not all combustible materials in the external walls of new residential buildings, hospitals, residential care premises, dormitories in boarding schools and student accommodation, as long as all of these are over 18 metres. The government in England has since announced proposals to go further by lowering the current 18 metre height threshold to 11 metres, extending the combustibles ban to hotels, hostels and boarding houses, and introducing a complete ban on unsafe ACM with an unmodified polyethylene core for use on any building. England will also finally follow Scotland and Wales in requiring sprinklers in new residential buildings over 11 metres high (instead of 30 metres). However, the current ban and plans do not apply to existing buildings and the government is acting slowly to address the issue of the toxicity of building materials. We need a total ban (with retrospective application) on combustible materials in the external walls of all multi-occupied buildings. There also remains no legal requirement for fire extinguishers, central alarms, and second means of escape as stay put remains the default policy.

Alongside the public inquiry, an Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety was launched in 2017 under Dame Judith Hackitt, the former Chair of the Health and Safety Executive. This has produced important changes for improving high-rise safety currently being taken forward into legislation. These include the creation of a new Building Safety Regulator to oversee and enforce a new safety regime with stronger civil and criminal enforcement powers over named dutyholders who will have clear legal responsibilities at each stage of the building’s life-cycle. New buildings will also need to have a building safety certificate before occupation can commence. High-rise residents will have a direct route to the Regulator to voice their safety concerns and a means for them to report serious safety issues is being progressed through a revamp of the CROSS system (Confidential Reporting On Structural Safety) administered by the Institutions of Structural and Civil Engineers, and the Health and Safety Executive.

We have written elsewhere about some of the problems with the Hackitt-based regulatory system, but the most fundamental is that it will initially only include new-build high-rise residential blocks of 18 metres or higher. This makes no sense as made clear by the horrifying fires in 2019 to sub-18 metre buildings at Barking Riverside (timber cladding and balconies), the Cube in Bolton (part timber frame, flammable HPL cladding), Worcester Park (timber frame), Beechmere retirement complex in Crewe (timber frame) and a hotel at Cribbs Causeway in Bristol. These and thousands of other existing blocks of flats below 18 metres with potentially serious safety failings must be urgently placed in a more stringent regulatory system. The government has effectively conceded the point in its decision to ban combustibles and require sprinklers in new buildings above 11 metres.

Alongside changes to existing building regulations, the government also set up a Building Safety Programme in 2017 to take immediate safety measures — principally the testing and removal of combustible cladding on other tower blocks. As Pete Apps, the exemplary journalist at Inside Housing has shown in forensic detail, the entire process has been an unmitigated disaster from the start caused by government intransigence, incompetence and — once again — an ideological bias against government intervention in the market. The outcome is that three years on from Grenfell, 300 of the 455 high-rise residential buildings and publicly owned buildings found to have dangerous ACM cladding are still wrapped in it; and a further 1700 high-rise buildings are covered in other (non-ACM) forms of combustible cladding and fire safety defects, putting an estimated 53,000 households at daily risk of a catastrophic fire.

One of the main reasons for the shocking scale of inaction is that while the government quickly made funding available for social landlords to replace ACM cladding, it initially refused to support the private owners (or freeholders) of high-rise buildings, telling them to ‘do the right thing’ and foot the bill. However, the vast majority of freeholders — which include many offshore ground rent speculators — have simply used their legal powers to recharge the costs of temporary fire safety measures (like waking watches) and any building works to their ‘leaseholders’ who bought flats and normally live in these developments. These residents have faced enormous bills running to six-figure sums, with their homes frequently valued as worth nothing [£0] on the housing market, leaving them unable to sell or remortgage to finance their exorbitant bills, and thus effectively trapped in unsafe buildings with appalling mental health effects.

Nevertheless, the response by these residents to these injustices — with support from the Grenfell community — has been remarkable. Concerted political campaigning, spearheaded by the UK Cladding Action Group (UKCAG) and the Manchester Cladiators with support from the Leasehold Knowledge Partnership, forced the government in 2019 to make £200 million available to fund ACM removal works in private buildings, followed by a further £1 billion fund in March 2020 to support the costs of non-ACM cladding. However, a recent investigation by a committee of MPs found stringent rules on applying to the Fund “risks leaving many unable to access vital funding” and that a sum closer to £15 billion is required to to carry out remedial work on all buildings that currently have dangerous cladding and other fire safety issues, including inadequate fire doors or missing fire breaks.

Finally, we turn to the issue of evacuation from high-rise buildings. The Grenfell public inquiry has made two highly significant and welcome recommendations in this regard: first that the government should “develop national guidelines for carrying out partial or total evacuations of high-rise residential buildings” including procedures for evacuating disabled and older people; and second, that the owner and manager of every high-rise residential building should be “required by law to prepare personal emergency evacuation plans (PEEPs) for all residents whose ability to self-evacuate may be compromised”. These recommendations are no doubt contributing to the widespread changes being rolled out in firefighter high-rise incident training across the country with a focus on prioritising the protection of the stairs. Such an approach is not new as Kent Fire and Rescue Service have been using portable fans and smoke curtains to do it successfully for the past ten years. Residents across London will doubtless be asking why the LFB was not using this strategy in 2017 and what a profound difference it would have made if they had been.

At the same time, just as with the Lakanal House disaster, there appears to be a major effort by the landlord lobby to resist the public inquiry’s recommendations on the need to develop evacuation strategies. A new Code of Practice (CoP) is currently being prepared at the behest of the housing sector through the British Standards Institute (BSI) by C.S. Todd and Associates Ltd — the authors of the 2011 LGA Guide — that will apply to all fire risk assessors and enforcing authorities like the fire and rescue service, every time they assess residential high-rise buildings. The new CoP is being put together by a small, shadowy group of landlords, fire engineers, and Chief Fire Officers without any accountability or scrutiny. Its contents suggest that the intention of the landlord sector is to cling on to stay put as the default evacuation strategy. Specifically, in response to the public inquiry’s positive recommendations, the draft COP states that it is not “normally practicable” for a building owner or landlord to make special arrangements for evacuation of disabled residents in the event of fire and that it is “wholly unrealistic” to expect the housing provider to prepare and update Personal Emergency Evacuation Plans for such residents in the event that the fire brigade deems their evacuation to be necessary. By using the official stamp of approval from the British Standards Institute which acts as the main authority on regulatory good practice, this COP will enable building owners and landlords to completely circumnavigate the public inquiry’s recommendations, saving themselves a lot of money in the process.

There are of course many more aspects of the post-Grenfell response by government and industry that deserve attention. It is therefore vital that we all remain vigilant as opportunities to improve safety regulations governing the built environment do not come along very often. Over the coming months, as the public inquiry restarts, we will be doing whatever we can to shine a spotlight on those seeking to subvert the housing safety movement and support Grenfell United, UKCAG and other resident-led bodies in their quest for ‘truth, justice, and change’.

Stuart Hodkinson is Associate Professor of Critical Urban Geography at the University of Leeds and the author of Safe as Houses: Private Greed, Political Negligence and Housing Policy after Grenfell (Manchester University Press, 2019). He can be contacted on s.n.hodkinson@leeds.ac.uk; for more information, see www.safe-as-houses.org

Phil Murphy is a former Greater Manchester firefighter and Fire Prevention Officer (1997-2009) and now acts as an independent consultant advising landlords and responsible persons in relation to fire safety management of tall residential buildings. Having also been a resident in three separate high rise blocks of flats Phil Murphy has campaigned ceaselessly for improvements in fire safety and fire safety management of tower blocks. He can be contacted on phil@manchestersustainablecommunities.com

Photo credit: Andy Mitchell, Flickr.

17 June 2020